Remembering a historic event 20 years ago today

Aug 29, 2025

In January 1996, myself, my wife and our 2 year old daughter arrived in Jackson, Mississippi. I had been a meteorologist with the National Weather Service for a little more than 5 years, and had been transferred from Cleveland, OH when I was selected to be a senior forecaster at the Weather Service Forecast Office in Jackson. After 5 years of cloudy, cold, snowy winters, January in the Deep South was a revelation for all of us, and I soon became enthralled as a scientist with the challenging weather of the Southeast. We didn’t know it then, of course, but we ended up staying in Mississippi for the next 20 years and the state would be where our daughter and soon to arrive son would call “home.”

Fast forward to the summer of 2005. By then, I had worked my way up the Jackson office’s structure and had become the meteorologist-in-charge (MIC) in 2002. Our service area stretched from northeast Louisiana and southeast Arkansas across central Mississippi. I of course by then had become quite familiar with the region’s active weather, but didn’t know that the weather leading up to my becoming MIC was preparation for the main events.

While our service area did not include the Mississippi Gulf Coast, we were the NWS office in the state’s capital city, and our office was the “state liaison” office. This meant that whenever a tropical system threatened the Gulf Coast, we would spin up tropical operations to support the state agencies, particularly the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency (MEMA). We of course also had to deal with the inland impacts from any landfalling system, and with our service area extending to the Hattiesburg area about 50 miles from the coast, we had serious impacts with any significant tropical system.

The tropics had not been particularly active during my first several years in Jackson, with Hurricane Georges in 1998 being the main “event,” but even that had been a relatively glancing blow for our area. Things started to ramp up soon after I became MIC in August 2002, with Hurricane Lili intensifying to a category 4 in the Gulf and luckily weakening before making landfall in Louisiana but still causing significant impacts in our area. This was followed in 2004 by Hurricane Ivan causing major impacts in our area.

2005 was the year it would truly all change — the hyperactive Atlantic hurricane season that would be the first to go through the entire list of names and have to start using Greek letters. The central Gulf Coast would be impacted by multiple hurricanes: Cindy, Dennis, Rita. Of course, though, the one that literally impacted the course of our nation was the one that made landfall 20 years ago today: Hurricane Katrina. I want to take you through that event as I experienced it as the NWS meteorologist in charge of serving the state of Mississippi.

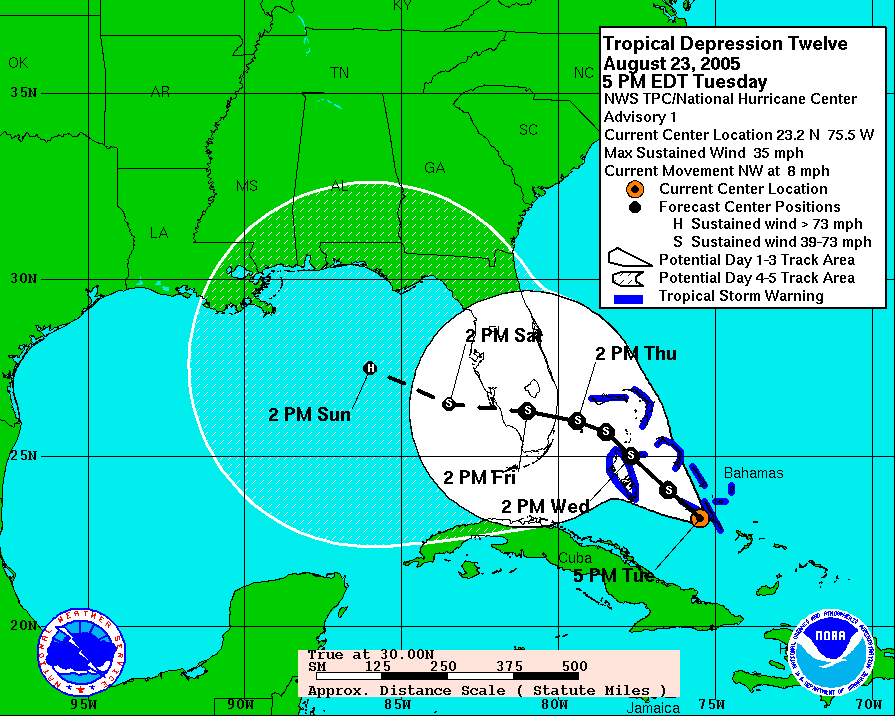

The initial advisory for the system that would become Katrina was issued by the National Hurricane Center at 5 pm ET on Tuesday, August 23, 2005. We had been closely watching the remnants of Tropical Depression Ten, which had dissipated in the Lesser Antilles several days earlier, move northwest toward Florida. While weather models were much less advanced 20 years ago than today, there were hints that a tropical system could redevelop out of the remnants, and with this advisory, the NHC determined that the remains of TD 10 had merged with another system and become Tropical Depression Twelve over the eastern Bahamas. Conditions were expected to be favorable for intensification, and NHC forecast it to become a hurricane in the central Gulf in 5 days after crossing Florida.

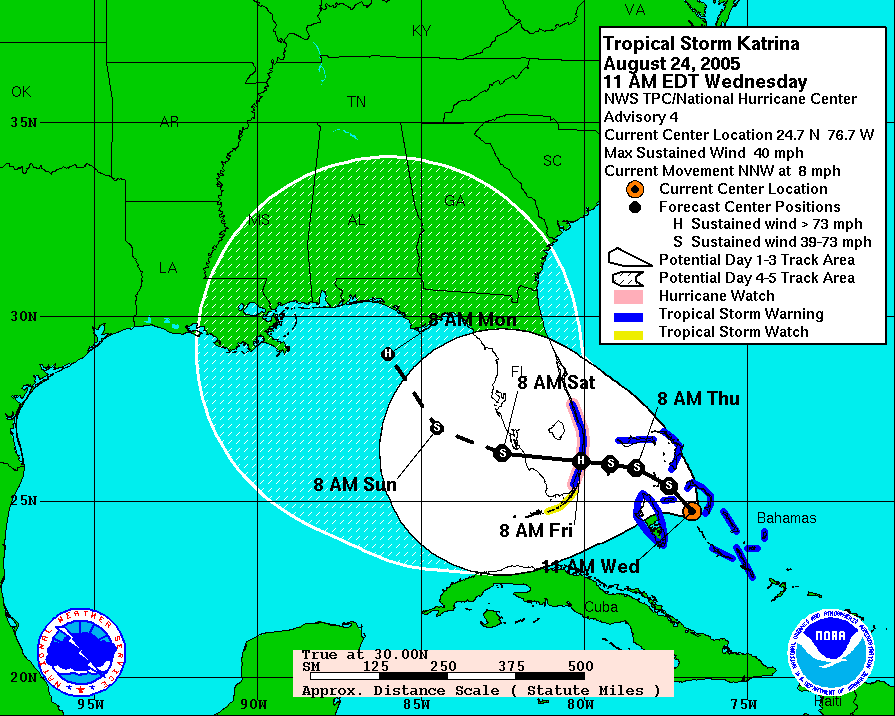

By the next morning, the system had intensified into a minimal tropical storm, Katrina. NHC noted in their forecast discussion that the system looked to be getting better organized and forecast it to become a hurricane before it reached the east coast of Florida. At this point, the global computer models — the US Global Forecast System (GFS) and European Center for Medium Range Forecasting (ECMWF), the same main ones we use today (but less sophisticated then) — were picking up on Katrina and showing it turning more northwest once it crossed Florida. Of course, forecasts were not nearly as accurate 20 years ago as today, and the NHC cone of uncertainty — which is based on the average historical forecast error — was much larger then. South Mississippi was clearly in the 5-day cone at this point.

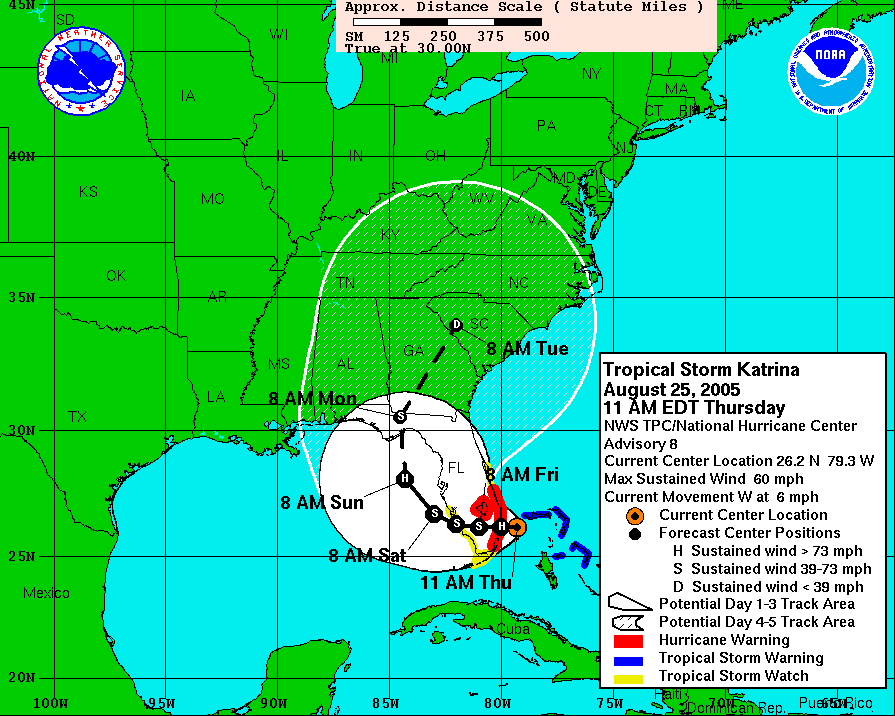

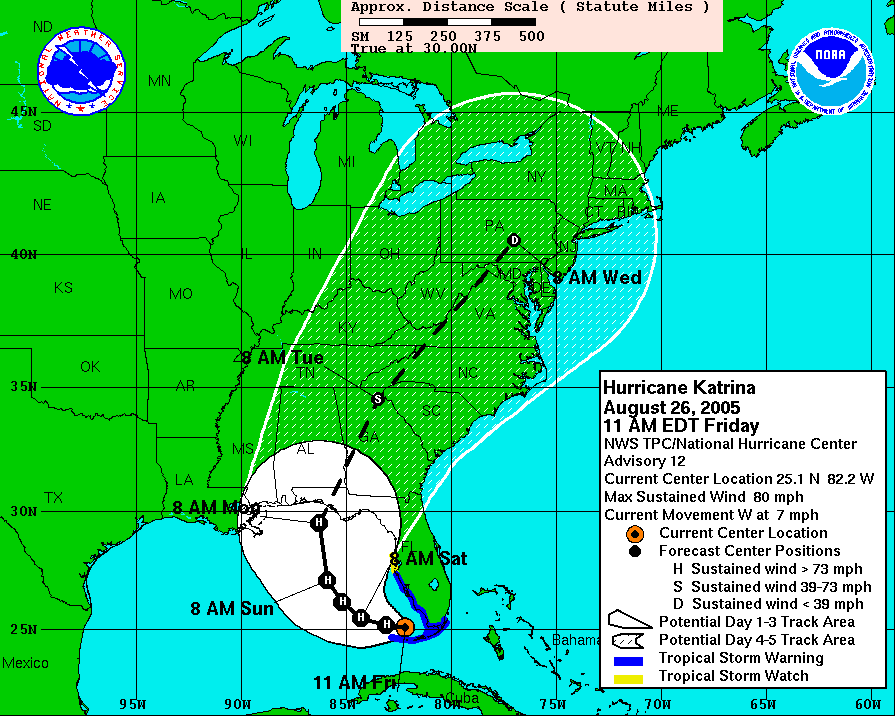

The forecast evolved significantly over the next 24 hours. The global models had trended toward a much quicker northward turn of Katrina after crossing Florida, and only had it tracking over the northeast Gulf for about 36 hours before making a second landfall over the Panhandle. However, in their discussion with the 11 am ET advisory shown above, NHC noted that the GFDL model — the only true tropical atmospheric model at that time, developed by the NOAA Research Global Fluid Dynamics Laboratory — actually showed Katrina moving southwest across the Florida Peninsula and then making a much larger loop over the Gulf toward the Florida Panhandle. For Mississippi, at this point only the extreme eastern portion of the state was even in the NHC forecast cone.

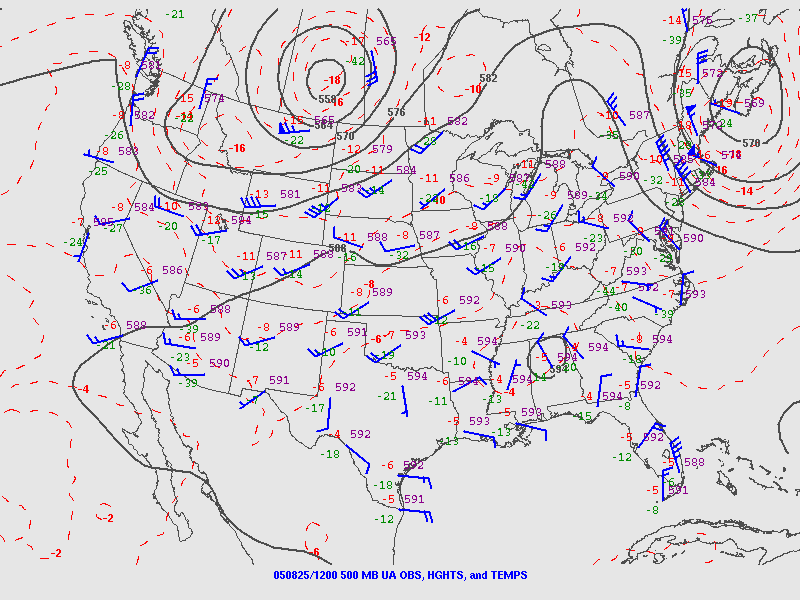

Myself and the team of meteorologists at NWS Jackson were still concerned for our area. The upper air weather map for 500 millibars — about 18,000 ft AGL — on the morning of Thursday, August 27 (above) was showing a rather strong area of high pressure centered over Alabama, with north to northeast mid and upper level flow across Florida. Even today, the models can underestimate the strength of these upper level high pressure areas (we saw that recently with Erin tracking farther west than anticipated), so the GFDL solution of a farther west track was concerning. We were at this point sending e-mail briefings to our emergency management and government partners and telling them while a direct track toward Mississippi was a low probability scenario, part of the state was still in the cone and we had enough uncertainty that people needed to monitor the situation closely.

My hackles started really getting up on Thursday evening as Katrina passed across the Florida Peninsula. Instead of moving west to west-northwest as was forecast (check out forecast map above), it was clearly moving southwest as you can see in this radar loop. This immediately elevated my concern that the GFDL model was onto something with its track farther west and with more time over the Gulf. Furthermore, by Thursday evening the GFDL was explicitly intensifying Katrina to a major hurricane, and the ECMWF global model showed the hurricane deepening to 961 mb over the Gulf, very strong for a global model at that time. Katrina had become a hurricane just before landfall, and amazingly was still a hurricane when it moved offshore. This suggested a robust internal structure as well as a very favorable atmospheric environment — something that is often the case when a storm moves west to west-southwest underneath a strong upper level high as Katrina was doing.

Friday, August 26, 2005 was the first of a few different days from the Katrina period that will be etched in my memory as long as I am around. While the forecast had not changed much that morning, with landfall still forecast over the central Florida Panhandle, it had shifted far enough west to bring more of eastern Mississippi and southeast Louisiana into the NHC cone.

More concerning though was what the observational data was telling us. The Key West radar had a good view of Katrina and showed that it was intensifying with the eyewall trying to close off. This intensifying trend was also supported by reconnaissance aircraft which showed the pressure down to 971 mb with winds up to 100 mph by midday. Perhaps the most crucial concerning trend was that Katrina was still moving southwest – suggesting that the upper level high pressure area to the north was stronger than forecast and that a farther west movement was becoming more likely.

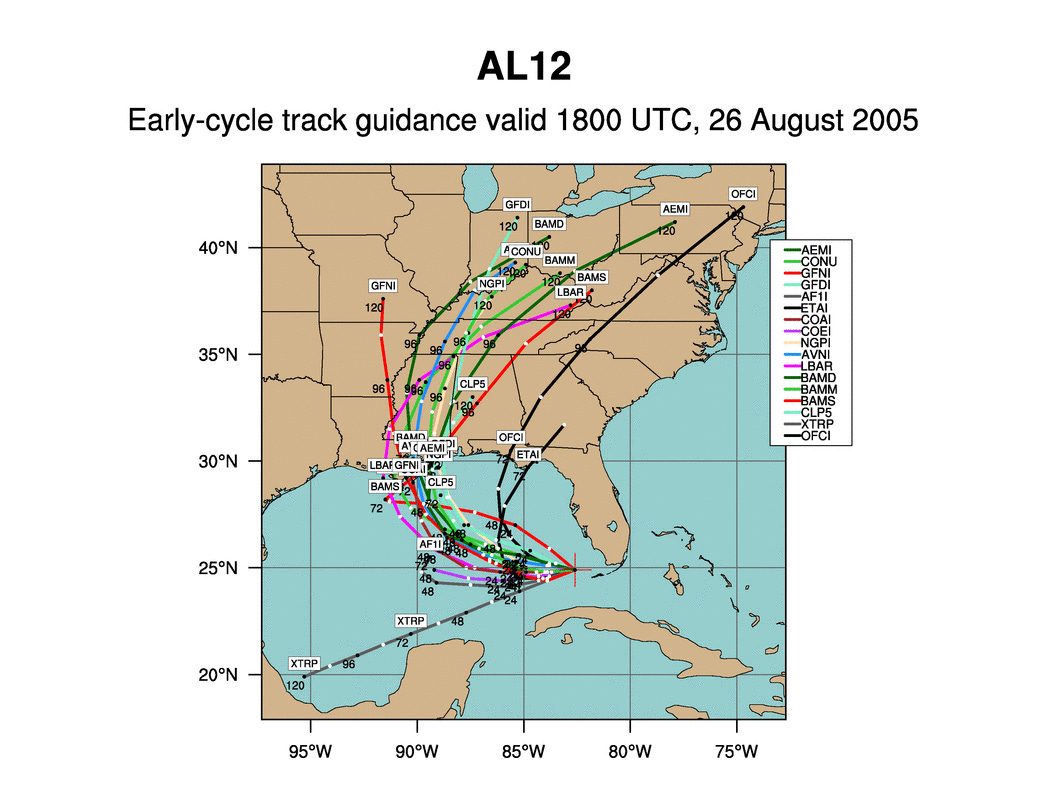

What I will remember from this day more than anything was when the new global model data started arriving from late morning through early afternoon. As shown in the spaghetti model plot from midday on that day, all of them unanimously shifted the track substantially west and had landfall somewhere over southeast Louisiana or the Mississippi Gulf Coast. I will never forget sitting in my office and hitting refresh on the website where I could get the earliest look at the latest ECMWF model, and seeing it having as large and intense of a cyclone as I had seen in a global model forecast over the north central Gulf of Mexico in 48 hours.

Knowing that it was a Friday afternoon and that people were not truly anticipating a direct hit as far west at Mississippi or southeast Louisiana, we started doing what we could to get the word out. Obviously we could not get ahead of the NHC forecast, but we did start making phone calls to key partners like MEMA and county and municipal emergency managers, letting them know that the NHC forecast would likely shift substantially west later that afternoon and that the threat of a large, dangerous hurricane making a direct impact somewhere in our region was significantly increasing.

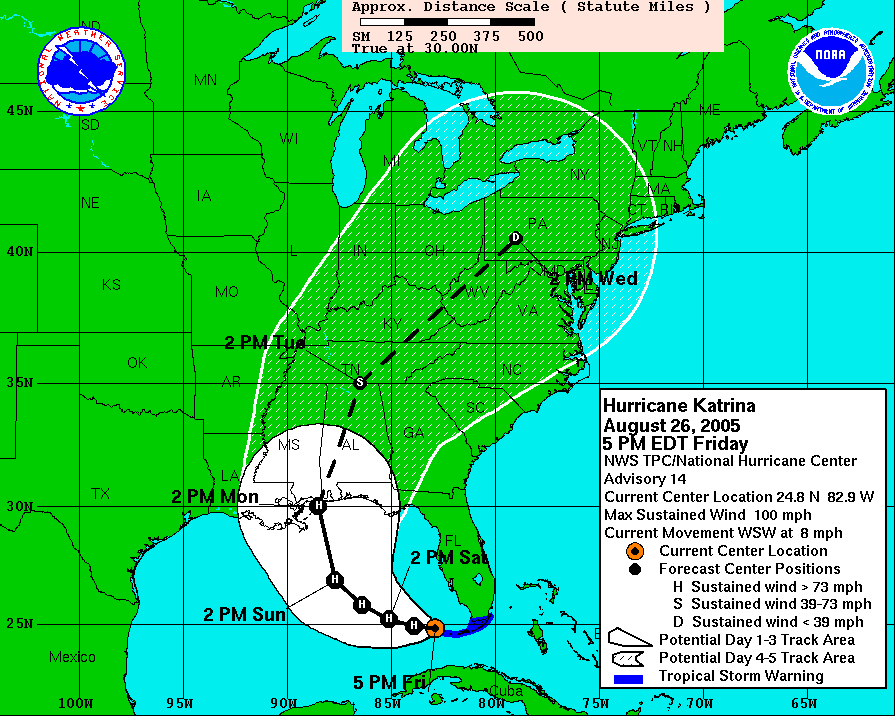

Indeed, when the 5 pm ET advisory came out that afternoon, it shifted the track well to the west, with the landfall point shifting from near Panama City to the Mississippi/Alabama state line. NHC does not like to make huge changes in the forecast from one cycle to the next as it can cause a “windshield wiper” effect that could cause public uncertainty and confusion. Given that, they did not shift the forecast as far west as the model forecasts might have suggested — but noted in their discussion that landfall was still 72 hours away and further shifts were likely.

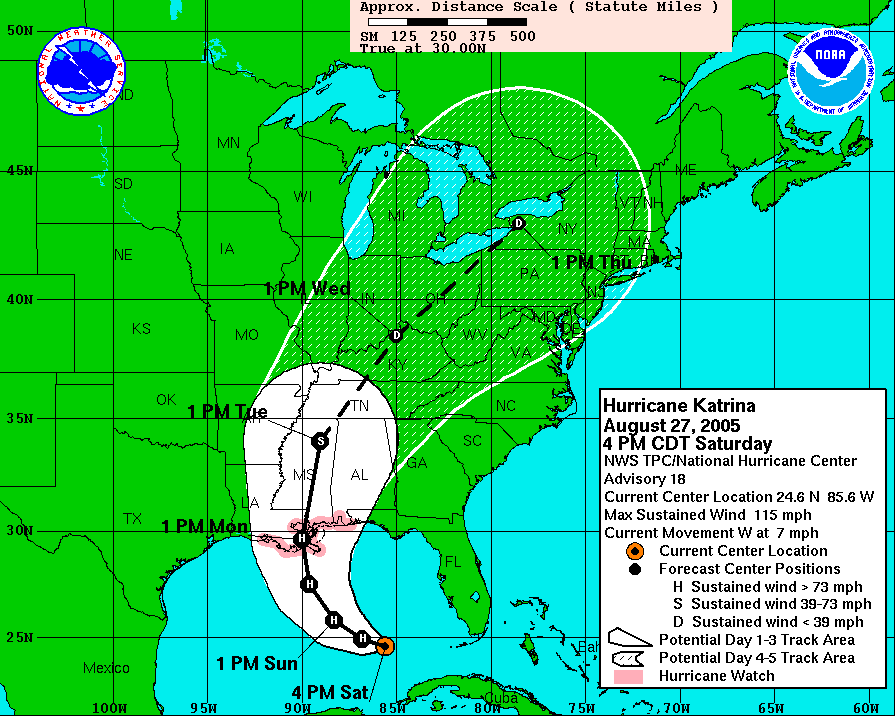

Saturday, August 27 was the day in which preparations for a direct landfall in southeast Louisiana and Mississippi really ramped up. Katrina intensified to a major hurricane, and for the first time in discussions NHC mentioned the possibility of Katrina becoming a category 5 hurricane at some point before landfall.

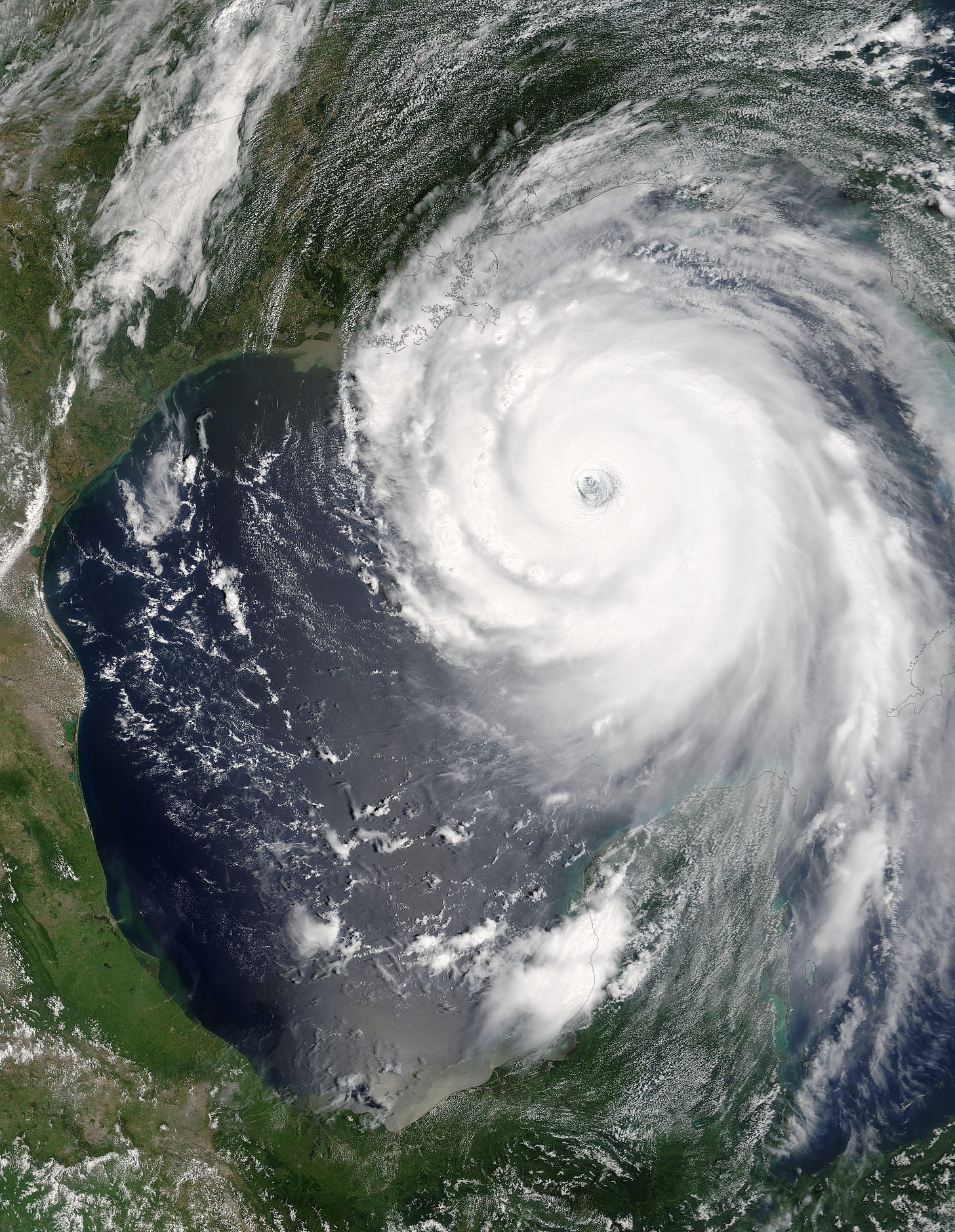

Sunday, August 28 dawned with the terrifying sight of a huge category 5 hurricane poised in the north central Gulf of Mexico and heading northwest. Overnight the central pressure of the hurricane had plunged to 908 millibars, one of the deepest Atlantic hurricanes on record, with reconnaissance aircraft measuring winds at flight level of 175 mph, equating to 160 mph at the surface. NHC stated in their discussions that day that the exact intensity at landfall would probably mainly be driven by internal changes in the storm such as concentric eyewalls — what we today know as eyewall replacement cycles — but it would be a large and dangerous hurricane at landfall on Monday.

For myself and the rest of the meteorologists at NWS Jackson — and I am sure at other NWS offices in the region such as New Orleans/Slidell and Mobile and many broadcast meteorologists — we quickly realized that this day was going likely be the most important day of our career, and one in which we could truly be influencing whether people lived or died over the next couple of days. I will never forget our warning coordination meteorologist and I sitting in my office that afternoon discussing messaging; he literally broke down in tears as he talked about knowing how many people would likely be dead 24 hours later.

One talking point that we discussed with regard to messaging that day was comparisons to Hurricane Camille. Camille was still the benchmark hurricane for Mississippians and mentioning it would get people’s attention and concern — however, it was clear at that point that regardless of what intensity Katrina made landfall at that it would be a much larger hurricane than Camille, meaning that storm surge and wind damage could encompass a much larger footprint than Camille. We tried to emphasize that in all of our partner briefings and media interviews to try to ensure that people understood that from a damage perspective Katrina was likely to be much more impactful than Camille. In the Hurricane Local Statement that myself and one of our senior forecasters issued that afternoon, we said:

PREPARE FOR THE POSSIBILITY OF PROLONGED POWER OUTAGES OF

SEVERAL DAYS TO PERHAPS A FEW WEEKS. PEOPLE RESIDING IN HOMES THAT

ARE NOT WELL CONSTRUCTED WILL WANT TO MOVE TO SAFER ALTERNATIVE

LOCATIONS TO RIDE THE PASSAGE OF THE STORM OUT...PARTICULARLY OVER

AREAS SOUTH OF INTERSTATE 20 AND EAST OF INTERSTATE 55 WHERE THE VERY

STRONGEST WINDS COULD OCCUR.

THE SERIOUSNESS OF THIS SITUATION CANNOT BE OVEREMPHASIZED

HURRICANE KATRINA NOW IS THE SAME STRENGTH AS HURRICANE CAMILLE

WHEN IT MADE LANDFALL IN 1969...BUT IS EVEN LARGER IN SIZE...MEANING

THE POTENTIAL DAMAGE MAY COVER A MORE EXTENSIVE AREA. PREPAREDNESS

ACTIVITIES SHOULD BE COMPLETED TODAY.

I went home late that evening, and have to say that I never spent a more sleepless night. I actually got up about 3 am and took a walk around our neighborhood and listened to the wind whistle through the pines while I thought about the devastation that was about to be unleashed on the region. Finally, even though the actual impacts for our area were not going to be until later in the day, I just went into the office.

Around 7 am CT on Monday, August 29, 2005, Katrina made landfall near Buras, LA. It was in fact going through an eyewall replacement cycle at the time of landfall, and in retrospective analysis it would be determined that it had weakened to a high end category 3 hurricane by that point. However, it had grown even larger in size, and its pressure at landfall of 920 mb was at the time the third lowest on record for a landfalling Atlantic hurricane.

If there was ever a day in my career where I would just summarize it as “all Hell broke loose,” this was that day. Obviously, we were hearing damage reports and talking to the NWS Slidell office, but the issuance of this flash flood warning by Slidell was what I remember as the first inkling of how bad things were about to get.

BULLETIN - EAS ACTIVATION REQUESTED

FLASH FLOOD WARNING

NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE NEW ORLEANS LA

814 AM CDT MON AUG 29 2005

THE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE IN NEW ORLEANS HAS ISSUED A

* FLASH FLOOD WARNING FOR...

ORLEANS PARISH IN SOUTHEAST LOUISIANA

THIS INCLUDES THE CITIES OF...NEW ORLEANS

ST. BERNARD PARISH IN SOUTHEAST LOUISIANA

THIS INCLUDES THE CITY OF CHALMETTE

* UNTIL 215 PM CDT

* A LEVEE BREACH OCCURRED ALONG THE INDUSTRIAL CANAL AT TENNESSE

STREET. 3 TO 8 FEET OF WATER IS EXPECTED DUE TO THE BREACH.

* LOCATIONS IN THE WARNING INCLUDE BUT ARE NOT LIMITED TO ARABI AND

9TH WARD OF NEW ORLEANS.

DO NOT DRIVE YOUR VEHICLE INTO AREAS WHERE THE WATER COVERS THE

ROADWAY. THE WATER DEPTH MAY BE TOO GREAT TO ALLOW YOUR CAR TO CROSS

SAFELY. VEHICLES CAUGHT IN RISING WATER SHOULD BE ABANDONED QUICKLY.

MOVE TO HIGHER GROUND.

A FLASH FLOOD WARNING MEANS THAT FLOODING IS IMMINENT OR OCCURRING.

IF YOU ARE IN THE WARNING AREA MOVE TO HIGHER GROUND IMMEDIATELY.

RESIDENTS LIVING ALONG STREAMS AND CREEKS SHOULD TAKE IMMEDIATE

PRECAUTIONS TO PROTECT LIFE AND PROPERTY. DO NOT ATTEMPT TO CROSS

SWIFTLY FLOWING WATERS OR WATERS OF UNKNOWN DEPTH BY FOOT OR BY

AUTOMOBILE.

LAT...LON 2992 9012 2994 9003 2987 8987 3001 8985

3004 8982 3008 8993 3002 9012

$$

This was when we knew that storm surge was likely breaching and/or overtopping levees within New Orleans proper. Obviously, we had no idea the magnitude, but we all knew that this was the worst fear as far as potential damage and loss of life in NOLA. What we also did not know — but were soon to find out — was that our NWS communications circuits ran through a comms hub in New Orleans that would soon be flooded out, cutting off our ability to send out forecasts/warnings or access the internet.

It was not too long after this that the surge started to really increase on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. One of the most terrifying and heartbreaking aspects of this event for myself and our staff was that we started getting phone calls from desperate people either on the coast or people who had relatives or friends on the coast. As people’s homes began to be overtaken by water, the 911 system became overwhelmed and they started calling anyone they thought might be able to help, including us. We tried to pass on reports to MEMA — but sadly there was little else we could do.

BULLETIN - EAS ACTIVATION REQUESTED

TORNADO WARNING

NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE JACKSON MS

ISSUED BY NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE HUNTSVILLE AL

1004 AM CDT MON AUG 29 2005

THE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE IN JACKSON HAS ISSUED A

* TORNADO WARNING FOR...

MARION COUNTY IN SOUTH CENTRAL MISSISSIPPI

LAMAR COUNTY IN SOUTHEAST MISSISSIPPI

* UNTIL 1030 AM CDT

* AT 1000 AM CDT...SPOTTERS REPORTED A TORNADO NEAR POPLARVILLE IN

PEARL RIVER COUNTY. THIS TORNAD IS MOVING NORTHEAST AT 50 MPH.

* LOCATIONS NEAR THE PATH OF THIS TORNADO INCLUDE...

LUMBERTON.

COLUMBIA.

HEAVY RAINFALL WILL OBSCURE THIS TORNADO. TAKE COVER NOW IF YOU WAIT

TO SEE OR HEAR IT COMING...IT MAY BE TOO LATE TO GET TO A SAFE PLACE.

LAT...LON 3075 8959 3089 8937 3139 8977 3128 9002

$$

CBD

By 10 am local time, we had lost our ability to communicate except via cell phone and occasional landline connections. Ironically, because our data came into our primary computer system (AWIPS) via satellite dish or direct connection to our radar, we were still getting all of the data we needed to perform services — we just could not disseminate anything. To say that the fact our office was in such a state on the most impactful weather day in the history of the region was incredibly frustrating is an understatement.

As you can see from the above tornado warning, our backup office in Huntsville began issuing our products for us. Unfortunately, even though we could see our radar data, it was not being transmitted beyond our office because of the comms failure, so Huntsville could not see our radar data for warning operations. In order to try to help coordinate the needed products, I set my office cell phone in operations, put it on speaker, the MIC in Huntsville did the same, and our staff described the needed warnings to the staff in Huntsville, who then issued them.

Over the next several hours as Katrina moved north, it remained a large and powerful hurricane well inland. Obviously as communications continued to break down and power loss became widespread, we lost the ability to have any real situational awareness about what had transpired as far as damage and casualties. The Mississippi National Guard and other emergency services would literally have to chainsaw their way through the downed trees on US Highway 49 and Interstate 59 to gain some semblance of access to the Mississippi Gulf Coast region over the next couple of days. It was only then that we began to get a sense of the devastation that had occurred to that area.

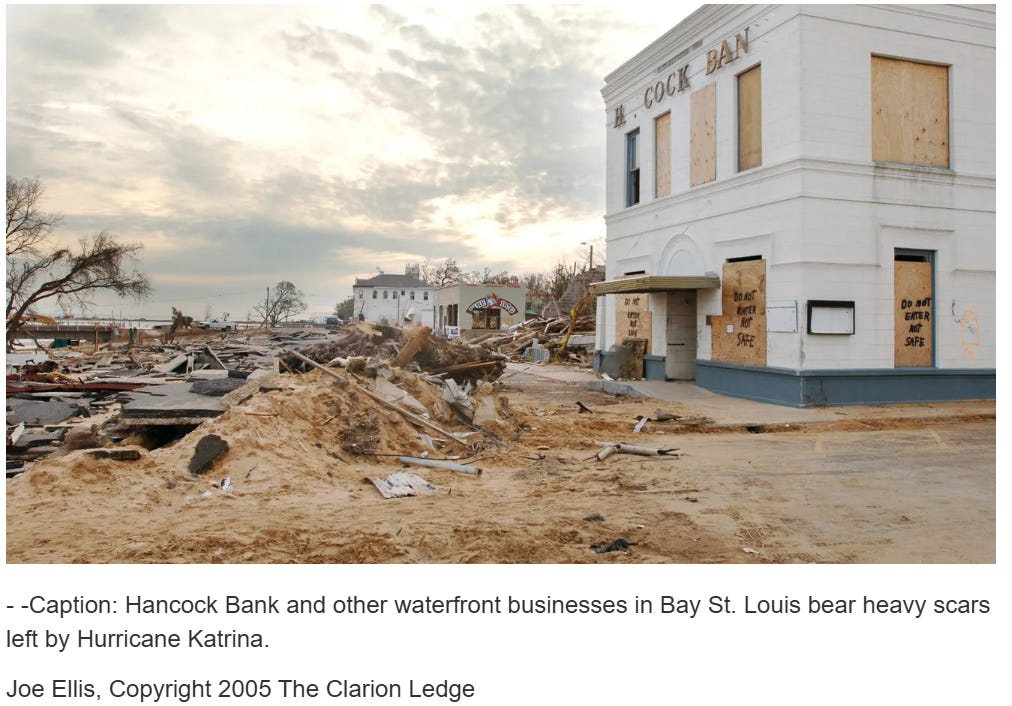

While New Orleans would rapidly become the focus of media coverage in the ensuing days, the destruction and loss of life that occurred in Mississippi should never be forgotten. At least 238 people lost their lives in the state, and the wind and particularly storm surge damage was devastating.

Several days after landfall, myself, our warning coordination meteorologist, and a couple of other staff members traveled along US Highway 49 and Interstate 59 to try to get some sense of the damage in our area, check in with some of our emergency managers, and eventually work our way to the Mississippi Gulf Coast, which the Slidell office could not access because of downed bridges. While we had gotten some sketchy reports by this point, we still did not have a clear picture of the damage.

When we finally worked our way to the Mississippi Coast, Bay St. Louis was the first area we reached. We stood in the area shown in this picture above. As I looked south, I was looking down on the Gulf, perhaps 15 feet below me, and I could look up on the buildings above me and see water marks above my head. We did not have the equipment to calculate actual water levels, but it would later be calculated to be near 28 feet at its highest point just west of us at Pass Christian. The awe — and terror — I felt in that moment when realizing the incredible power of nature and water is a feeling I will never forget.

And what is important to understand is that this damage was not limited to a small area. We stood in many locations along the immediate coast that day from Bay St. Louis to Gulfport and the back bay of Biloxi, and as far as you could see everything looked like what you see in the picture above. It was as if a giant violent tornado had impacted the region — but in fact it was the water of the Gulf that had produced this damage.

Obviously, in many ways I am just scratching the surface of what transpired during this period. For myself, as I look back it was undoubtedly the most stressful and challenging period of my career, but navigating it relatively successfully is also the accomplishment I am most proud of. Our staff faced career defining levels of challenges every day for a period of weeks, and I am incredibly proud of how well they rose to those challenges. A lot of conflict and emotion had to be navigated, and the mental health challenges for myself and the staff were not something I had anticipated going into this. I hope that one lesson that came out of this and other soon to follow historic level events for the NWS was the importance of having mental health support for staff dealing with events with massive damage and loss of life.

I want to finish this post by saying a word about the emergency management and emergency response services in Mississippi during Katrina. I already had tremendous appreciation for the incredible job these people did for the people of Mississippi, often with limited resources. Their awesome work during Katrina took my respect to a whole new level. I personally know of emergency management staff that were away from their homes for weeks as they worked to try to bring safety and comfort to so many people that had lost everything. It was the highlight of a career to be able to work in partnership with these servant leaders during such a defining event, and witnessing their efforts in August and September of 2005 is one reason I eventually decided to go back to school and get a master’s degree in emergency management. I will have more to say about the — sometimes painful — lessons that I felt we learned for national, state and local emergency management during Katrina — and my fears that we are rapidly forgetting those lessons — in a future post.

Note: NHC graphics are from their excellent archive of data available on their website. NWS products from Daryl Herzmann’s incredible IEM site.

Leave a comment