Recent New York Times article provides details about events at Camp Mystic

Nov 21, 2025

Over the last week or so, the July 4th flash flood tragedy in the Texas Hill Country has been back in the national news as several lawsuits were filed by the families of children and counselors that lost their lives at Camp Mystic, a Christian camp for girls located along the south fork of the Guadalupe River where 27 girls and counselors died. CNN did an in-depth story on the lawsuits that you can read here. In summary, the families are suing Camp Mystic for gross negligence:

“Tragically, due to lack of planning, the absence of any evacuation plans, lack of training, inadequate warning systems, and other acts and omissions of recklessness and gross negligence, Plaintiffs’ daughters suffered terrifying, brutal, and horrific deaths,” the lawsuit filed by the families of the six campers says.

A little over a week ago, I had the opportunity to visit Kerrville, TX and the areas along the Guadalupe River where the catastrophic flash flood occurred, and to talk to some of the local residents about their experiences during and after the event. Given this visit and some of the revelations from the lawsuits, I wanted to take another in-depth look at this event given what we now know four months after the tragedy.

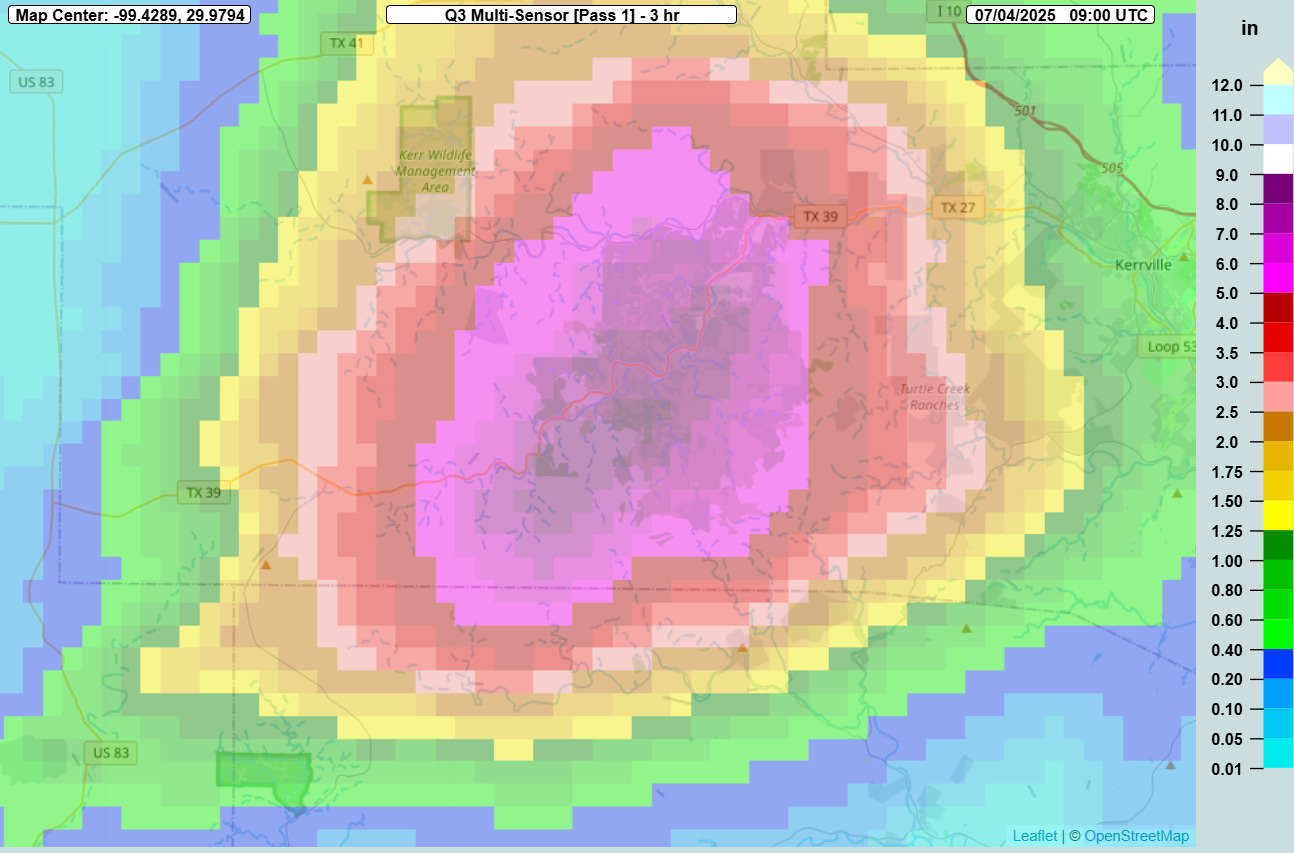

If you want a refresher on the overall weather situation, warnings and forecasts from the event, my posts from July 5 and July 6 provide much of that background information. In summary, rainfall of 6-10” in several hours fell on the south fork of the Guadalupe River, causing a catastrophic 30+ foot surge in the river that resulted in massive damage along the river channel and the loss of 119 lives. The bodies of two people have still not been recovered, and search and recovery efforts are ongoing months later.

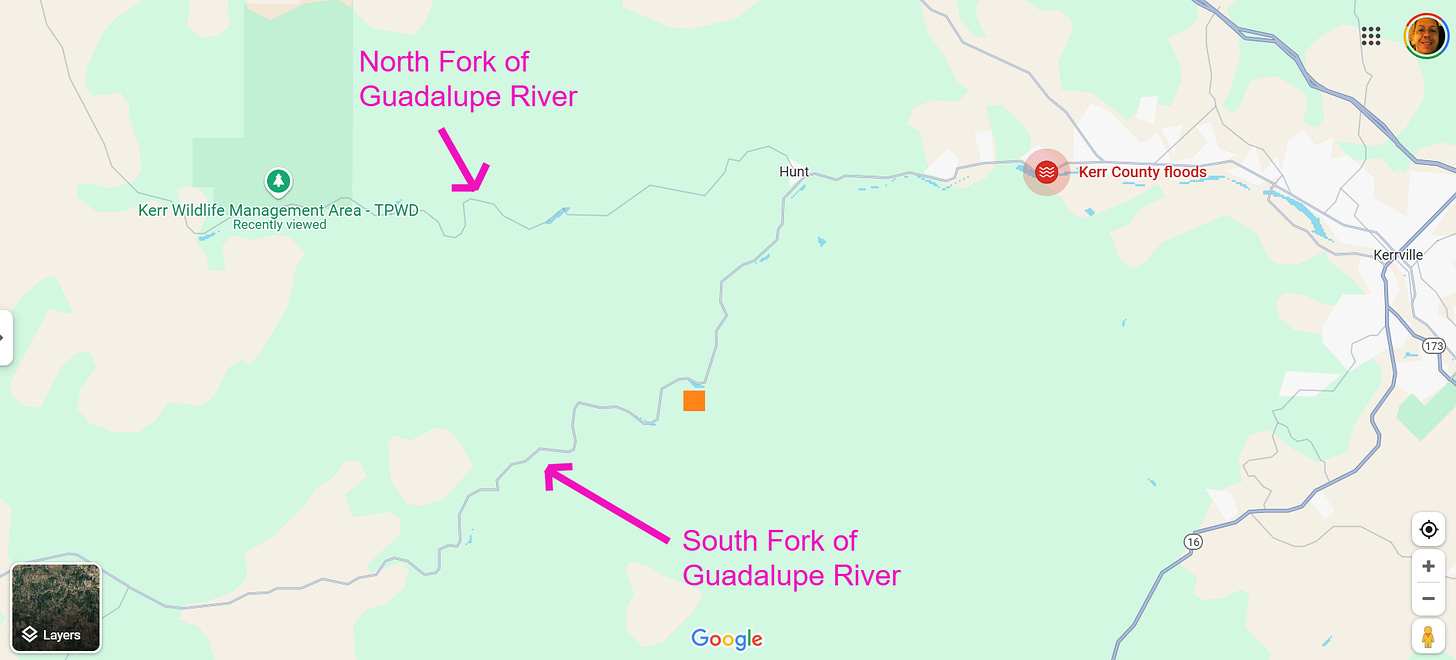

This map shows the general location where this flash flood occurred. Camp Mystic, the camp in the focus of the lawsuits I talked about above, is located along the south fork of the Guadalupe near the orange square on this map. Significant damage occurred all along the river down to Hunt, and then additional serious damage and loss of life occurred downstream of Hunt, particularly near Kerrville where RV and mobile home parks along the river were devastated and many lives were lost.

When we use the word “damage,” I think it is important to contextualize what we are talking about. This picture above is of the former location of the post office in Hunt, which was completely leveled by the flash flood. While certainly some cleanup around the area has occurred, talking to some of the first responders in the area they confirmed that the post office was one of several buildings along this stretch of the river that were completely destroyed and swept away, and that this area was completely unrecognizable in the immediate aftermath of the flood.

Here is a van that was likely rolled and battered with debris, and then deposited off the side of Texas Highway 39 that runs along the south fork of the river. I drove along this highway (the pictures are mine), and the damage was certainly some of (if not the) worst flash flood damage I have ever seen. There was clearly extremely high velocity flow of water 30 to 40 feet deep moving through the area, with stretches of trees leveled and a number of homes swept away. These scenes of slabbed buildings, mangled vehicles and intense tree damage reminded me of violent tornado damage that I have surveyed over the years. Like a tornado, the damage was not consistent, varying based on intricacies of the hydrology of the river — but where the most intense damage occurred, it was devastating.

The New York Times published on Sunday afternoon an article with a detailed timeline of the flooding at Camp Mystic and the desperate situation there that night based on interviews with the surviving employees (including the current owner) of the campground as well as pictures, phone records and hydrologic analyses by the risk management company First Street. I strongly encourage you to read this article to truly understand the horrific situation the staff and campers faced. The New York Times interviewed Edward Eastland, the son of the campground owner Dick Eastland who perished trying to evacuate campers during the flood. Edward was also working to evacuate campers that night, and was actually swept away and had to be rescued from a tree downstream from the camp.

Perhaps my biggest concern about this event has always been the apparent lack of preparation and planning for a significant flood in spite of the history of catastrophic flash floods along this river — and this lack of preparedness appears to have existed from the county government down to entities such as the numerous campgrounds and RV parks along the river. In this article, Edward Eastland admits that the campground did not have any plan for evacuating campers in the event of a flash flood, and that the evacuation of campers that did occur that night was completely improvised:

In interviews with The Times, Mr. Eastland and his brother Richard, who also works and lives at the camp, said that based on decades of experience living at the camp and running it through previous floods, they believed the cabins were the safest place for the campers.

“In our minds, the cabins were built on high ground,” Richard Eastland said.

The family felt that way even after a 2011 FEMA map placed most of the cabins, including Bubble Inn and Twins, within a 100-year flood zone. The camp hired surveyors who argued there were errors in the topography used for that map; the federal agency in 2013 removed the cabins from the floodplain maps.

But the July 4 flood had changed what high ground was for the camp, Richard Eastland said.

There had been no plan for how to evacuate campers, the Eastlands said. The evacuation was improvised, as the water level rose more rapidly than they had ever seen. The camp is planning to create an evacuation plan for the future, Richard Eastland said.

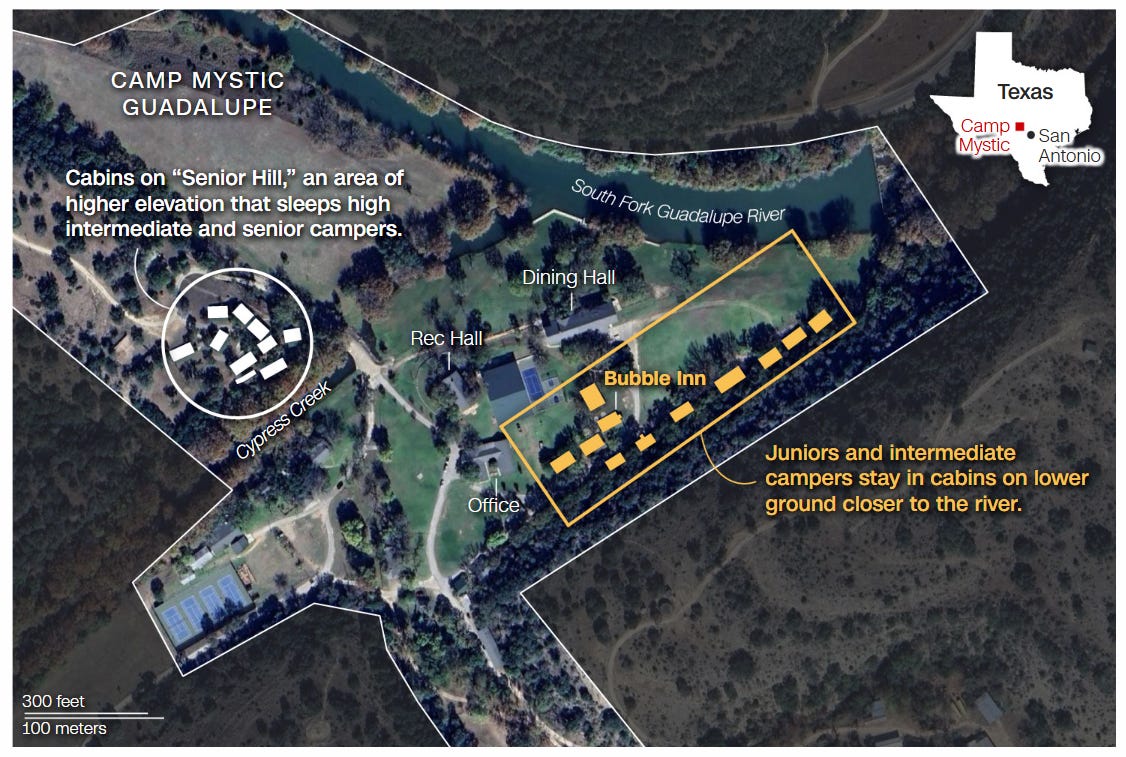

This map from CNN shows an aerial view of Camp Mystic, with the two areas of cabins for campers highlighted. According to the New York Times article, the fatalities occurred in the junior cabins closest to the rec and dining halls, Bubble Inn as identified on the map and the adjacent Twins cabins just above it.

This is a similar aerial view of the camp that I obtained from the FEMA Flood Map website, with the current FEMA flood insurance zones overlaid. To orient you, I have highlighted the Bubble Inn location with a white ellipse. This cabin sits just outside of the area with red diagonal hatching, which is the FEMA defined floodway. The floodway is the channel of the river that discharges the river’s “base flood,” which is defined as the flood with a 1% occurrence risk in any given year (or so-called 100-year flood). This area is heavily regulated to any sort of new development due to safety concerns but also to enable the river to convey its flood without additional obstructions or flow changes that could cause additional flooding or safety issues.

As you can see by comparing the FEMA map and the CNN map, Bubble Inn and the cabins along the road to its east — cabins which in some cases were successfully evacuated by the Eastlands or in which counselors ignored instructions to shelter in place and evacuated themselves and campers to higher grounds — are located in a flood zone designated as “Zone AE.” This means these locations are within the 1% flood occurrence risk, but are not considered in the maximum flood danger area subject to the most stringent regulatory requirements that exist in the floodway. This appears to be the area that was originally designated by FEMA as within the floodway but was removed on appeal by Camp Mystic as discussed in the NYT quote above and as reported by multiple media outlets.

Regardless of whether these locations were in the regulatory floodway or not (and Twins actually appears to be within the floodway), the cabins certainly appear to be within the area subject to flooding in a so-called base flood event, i.e., the 1% occurrence or 100-year flood. To me, as someone with expertise in meteorology and emergency management, it seems obvious that if one was going to house children in cabins in these areas, at a minimum there should have been well developed plans on how and when to evacuate those children. An expert in FEMA flood designations interviewed by the Associated Press also expressed concern:

Syracuse University associate professor Sarah Pralle, who has extensively studied FEMA’s flood map determinations, said it was “particularly disturbing” that a camp in charge of the safety of so many young people would receive exemptions from basic flood regulation.

“It’s a mystery to me why they weren’t taking proactive steps to move structures away from the risk, let alone challenging what seems like a very reasonable map that shows these structures were in the 100-year flood zone,” she said.

Pralle went on to note that even the survey the camp contracted for to use in its appeal of the original FEMA flood map showed that some of the cabins were only a few feet from the floodway, leaving no margin for error.

Based on comments made in the various articles about this event and conversations I had both during my weekend in Kerrville and in other venues since this event, it seems evident that there is a lot of misunderstanding about both the terminology used with regard to flooding and floodplains, as well as the likelihood of certain rainfall and flood events. The first point of concern surrounds the base flood elevation, i.e., the 1% occurrence flood or so-called 100-year flood.

Because of that latter term, many people think this is a flood that should occur once every hundred years. However, the term 100-year flood is really an expression of probability, not frequency. “1% occurrence flood” is a much more accurate way to describe it — again, this means that there is a 1% chance of this level of flood in any given year. To determine the risk of such a flood over a longer period of time, you have to aggregate those annual risks. Hence, over a given 50 year period, the likelihood of a 1% occurrence flood occurring is about 40 percent. In the NYT article, the Eastlands stated that that “based on decades of experience living at the camp and running it through previous floods, they believed the cabins were the safest place for the campers.” Unfortunately, decades of experience is simply not a long enough period to understand the risk of a given natural event like a flash flood — you can get “lucky” for decades, but the underlying actual risk is persistently present. Given the hydrologic modeling done by FEMA, these cabins were clearly located in an area at risk from the 1% occurrence flood.

It is also important to understand what being in a 1% occurrence flood area means as far as risk and potential impact varies based on the river and terrain. This map above shows the FEMA flood zones in the vicinity of Hannibal, MO along the Mississippi River. While we see the same Zone AE and floodway markings that we saw on the FEMA map for Camp Mystic, the meaning with regard to flooding impacts are very different.

Along a river like the Mississippi, a 1% occurrence flood will almost always be a slow evolving event with plenty of lead time for people to prepare, evacuate, etc. The rivers in the Texas Hill Country are completely different. They are some of the flashiest rivers in the country, subject to massive, high velocity flash floods capable of producing the damage I observed along the Guadalupe. Hence, the risk to life from a 1% occurrence flood is much greater along the Guadalupe than along the Mississippi.

The Guadalupe has suffered catastrophic flash floods in the past, and just 10 years ago a catastrophic flash flood with a rapid 40 foot rise of the Blanco River in the Hill Country killed 13 people near the town of Wimberley. While the July 4th flood was a record flood even greater than a 1% occurrence flood, the Guadalupe’s vulnerability to high velocity, rapidly growing flash floods means that the areas within the FEMA base flood (1% occurrence) zone are truly at risk for life threatening, rapid onset flooding. This is why it is hard for me to understand how flash flooding was not seen as a serious threat, not only by Camp Mystic but by other facilities along the river in or near the FEMA defined 1% flood occurrence area.

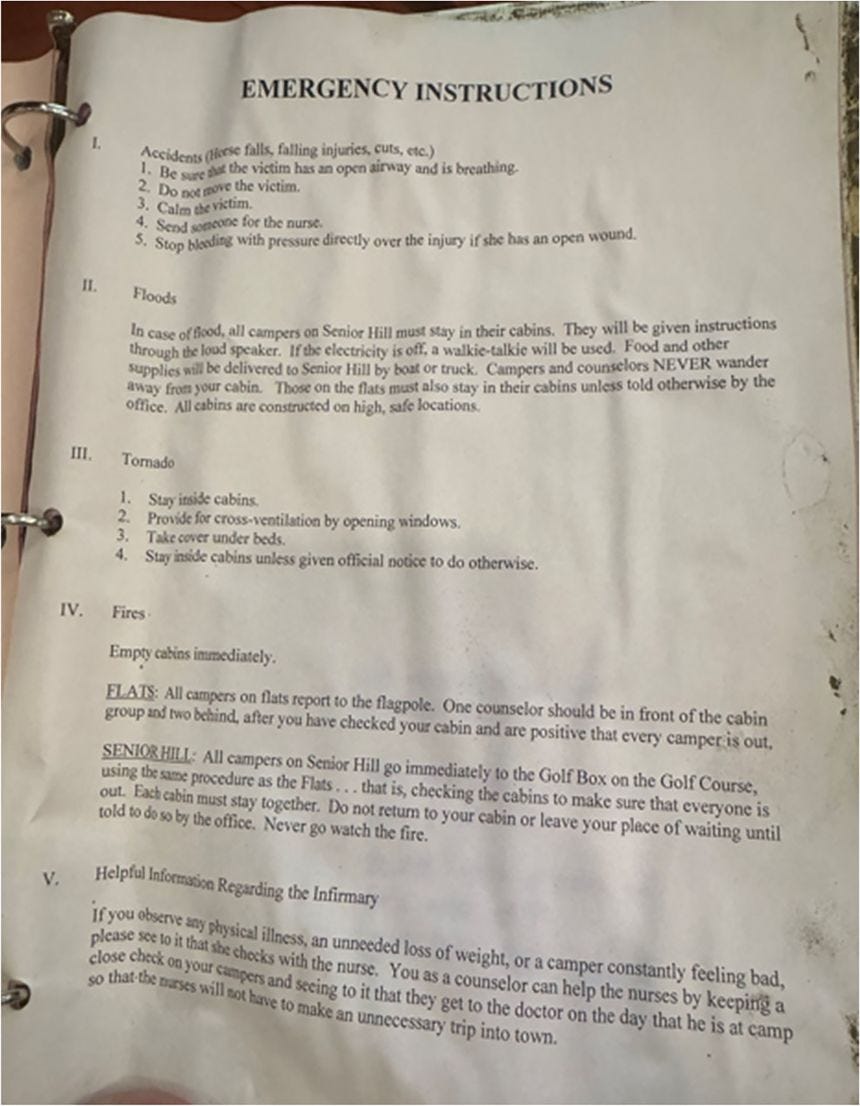

Clearly, though, it was not. Based on media reports, this is the entirety of the flood plan available to the counselors at Camp Mystic. The idea that campers would shelter in place for an ongoing flood is literally unbelievable to me — the first piece of advice in the event of a flash flood warning on the NWS flash flood safety website is “Get to Higher Ground: If you live in a flood prone area or are camping in a low lying area, get to higher ground immediately.”

While Edward Eastland said in the NYT interview that he did not tell anyone that night to stay in their cabins, the lawsuits filed by the campers’ families indicates that power and cell phone service were out, meaning counselors likely had to rely on the emergency plan and their own judgment. The NYT reports that two counselors did decide on their own to evacuate, climbing up a nearby hill with their campers; a third cabin evacuated with the help of the camp night watchman.

It is important, though, to recognize that where Texas Highway 39 crosses the river near Camp Mystic was likely the first spot to bear the full force of the massive flash flood, hence Camp Mystic was essentially the first and most vulnerable location impacted by the flood. However, even areas well downstream near Kerrville had significant loss of life even greater than at Camp Mystic.

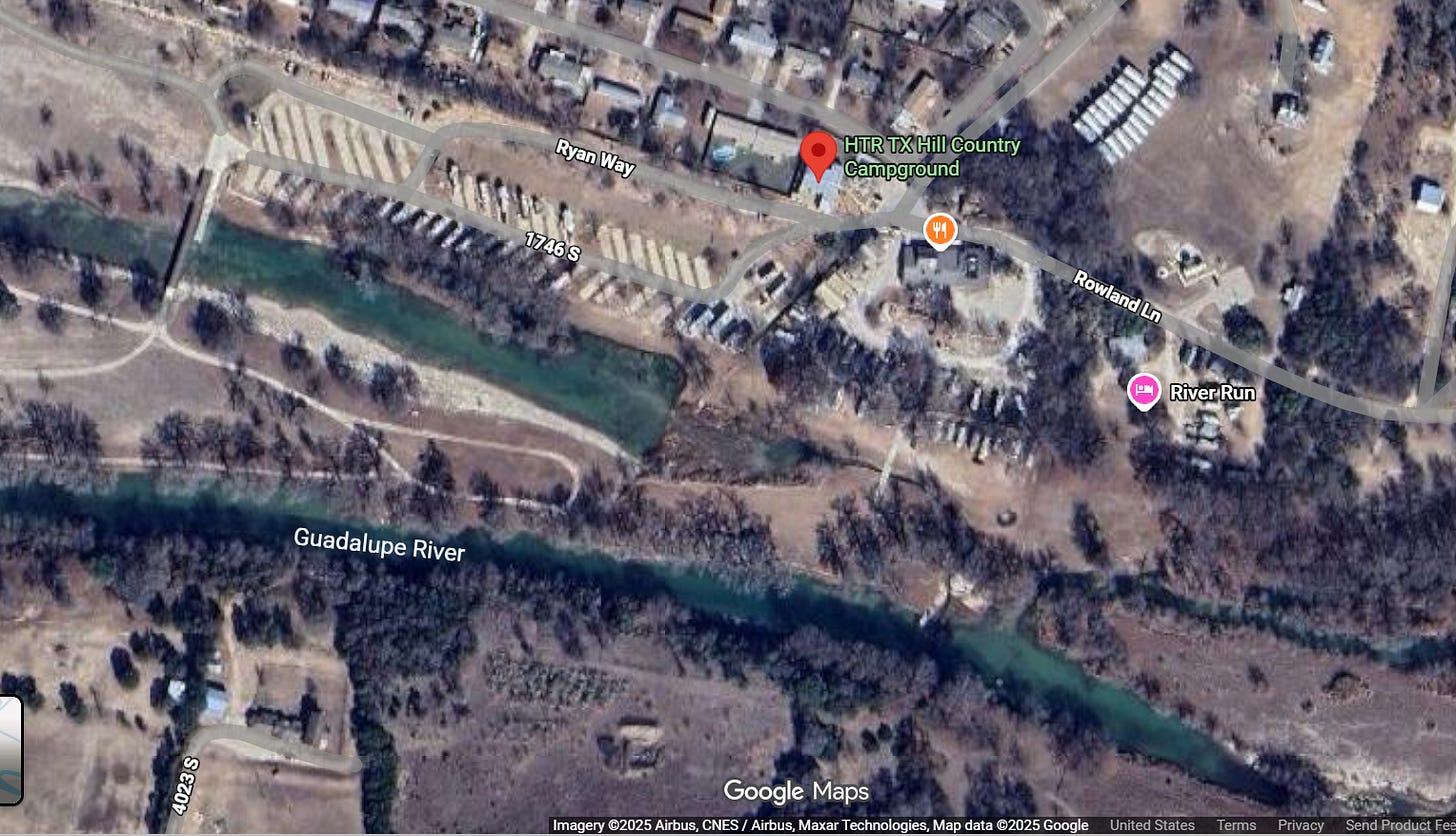

Dozens of people were swept away from the HTR Campground and nearby (across the street) Blue Oak Campground near Kerrville. Just as with Camp Mystic, both of these campgrounds are along the boundary of the regulated floodway but clearly within the 1% occurrence area. Even though these areas were farther downstream and thus had even more warning, catastrophic loss of life occurred, again suggesting a lack of awareness of the risk and associated planning or preparedness.

I also worry that people are overestimating the rarity of the rainfall that drove this flood and underestimating the likelihood of it happening again. This was undoubtedly a worst case scenario, with 7 to 9 inches of rain falling in 3 hours, centered right over the south fork of the Guadalupe River. This incredible amount of rainfall in such a short time period on top of the flashy terrain of the Hill Country was perfectly located to produce a catastrophic flood in this river channel. And certainly this was a relatively rare rainfall event — the NOAA Atlas 14 suggests that this amount of rain in a 3 hour period is somewhere between a .25 and .50 percent occurrence event.

While that sounds rare, when one sums this risk over a period of time, the threat becomes clearer. Over a 50 year period, there is approximately a 20% risk that this magnitude of rainfall will occur in the same location. That, of course, also assumes that we are living in a stable climate — which we are not. Just this week, the Washington Post published a story about how our warming climate is resulting in more frequent and heavier rainfall events in Appalachia, increasing flash flood risk there. While the WaPo study did not focus on the Hill Country, a similar evolution is certainly happening here. In my opinion, the 20% risk over the next 50 year should be viewed as the best case scenario; the actual risk is almost certainly higher, although how much higher will depend on climate change evolution in the coming decades.

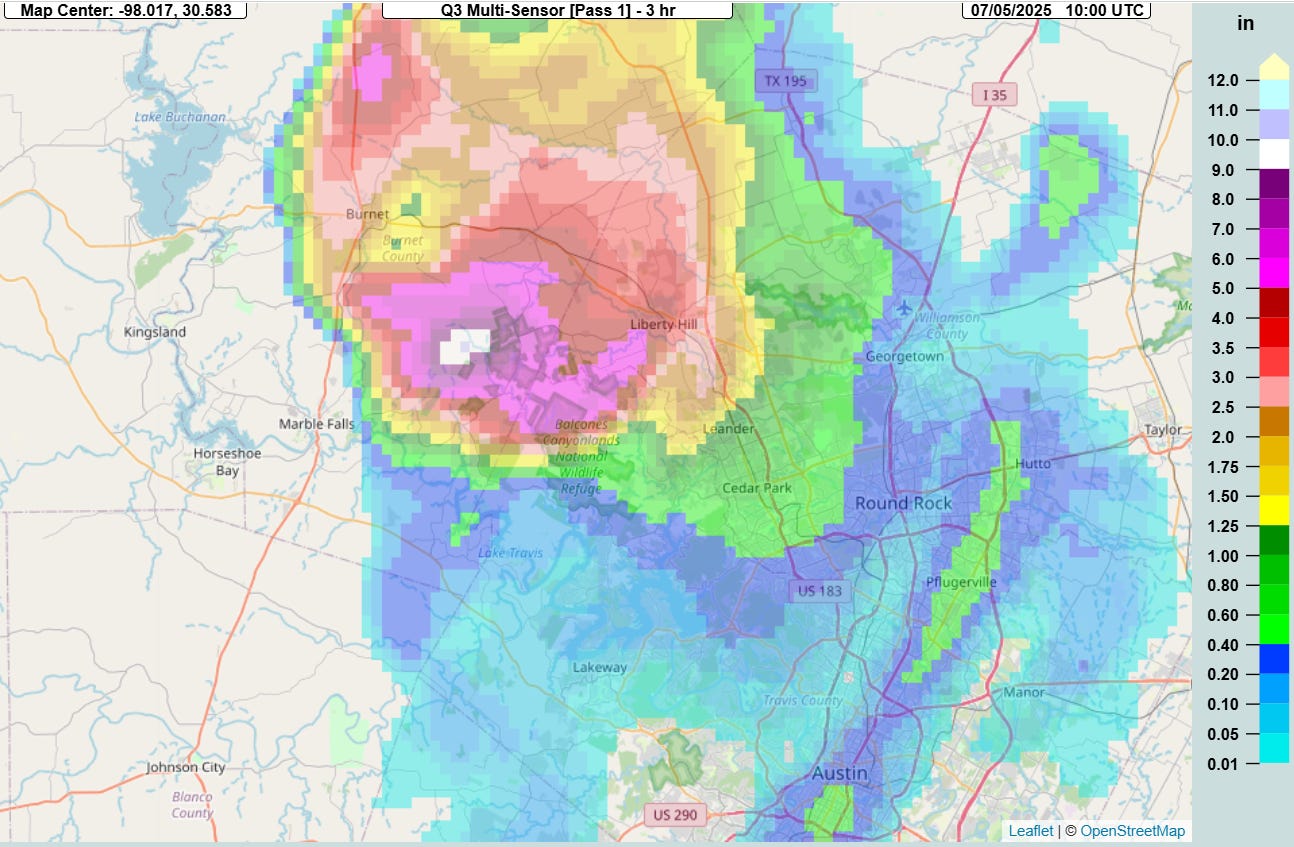

One must also keep in mind that when we say that the rainfall that caused this flood was a .25% occurrence event, we do not mean a .25% occurrence event for somewhere in Texas or for the Hill Country, we mean for the specific spot where it occurred. The following night after this catastrophe, even heavier 3-hourly rainfall than the Guadalupe flash flood fell to the just northwest of Austin, about 75 miles northeast of the prior night’s rainfall (above). This intense rainfall fell in the Colorado and San Jacinto river basins, causing major flash flooding that killed 17 more people.

I think it is important to understand that even though the July 4-5 period over central Texas was favorable for producing thunderstorms with intense rainfall rates, from my meteorological experience it was not a particularly unusual or rare setup for this part of the world. Moisture levels were near record levels for that that time of year, but to be honest, such high levels of moisture seems increasingly common from my perspective. The type of weather setup seen July 4-5 with large amounts of atmospheric moisture and subtle weather systems to produce repeat thunderstorm activity is not all that unusual for Texas — the maximum rainfall falling in exactly the right spot to produce such a devastating flash flood is what is less common.

The NYT article concluded with these poignant lines:

Edward Eastland said he has been going to counseling. He has returned many times to the spot where his father died along with several girls from Bubble Inn, at the base of a Cypress tree, by the now-gently flowing river.

“Every morning is horrible,” he said, his voice quavering. “I want to help the families. I don’t know what to do though.”

“We are so sorry,” said his wife, Mary Liz. “I feel like no one thinks that we’re sorry.”

I can only speak for myself, but I think this that these flash floods were a horrific event for everyone impacted and I feel incredible sympathy for the pain and grief that so many people are experiencing. However, the very horror of this night should compel us to examine what happened in a way that enables us to learn critical lessons that will help keep others from experiencing similar tragedy in the future.

My conversations about this event in recent months, and particularly those that I had in Kerrville, have convinced me that while people have an awareness of and respect for the dangers that flash floods present, there is a tremendous lack of understanding about the terminology, risk factors and technical aspects of flash flooding, even among government officials and professionals who have responsibility for public safety. Unfortunately, understanding these details about flash flooding can literally mean the difference between life and death, and with the threat to the public growing due to climate change and more people in harm’s way, it is critical that decision makers and the general public better understand flash flood risks and how they can be prepared for.

It is incumbent upon the meteorological, emergency management, social science and engineering communities to urgently work together to develop flooding terminology and educational materials that will help bridge the communication gaps that exist. While developing better science and installing improved alerting technology is also important, the takeaway lesson for me from July 4 has been that without the crucial first steps of improving communication and public education, science and technology advancements will not realize their full potential in reducing deaths and damage from these flash flood events.

We also have to recognize that these sorts of rapid onset flash floods place people into a chaotic and complex environment where life and death decisions have to made in seconds. This is why it is absolutely vital that facilities in vulnerable locations should have well researched emergency action plans that are developed in collaboration with emergency management professionals, and these plans should be practiced frequently by those responsible for activating the plan. Our society does not rely on flight attendants to make up an action plan for an in-flight emergency on a commercial airliner while the emergency is happening — we should not be relying on people to develop safety plans on the fly as flood waters are rapidly rising around them.

Leave a comment