Also: why the recent equatorial tropical activity could signal the demise of La Nina

Dec 01, 2025

Happy Monday and happy first day of December! December 1 is an important date in the meteorological calendar, as it means the end of fall for climatological record keeping and the start of the winter season. It also means that the Atlantic hurricane season has now officially come to a close, and with that and a lot of ongoing impacts globally from tropical systems, I am going to focus this newsletter on a look at the current tropics and a quick recap of the Atlantic season. There is also a lot of winter weather to talk about which will I will get to in an additional post this afternoon.

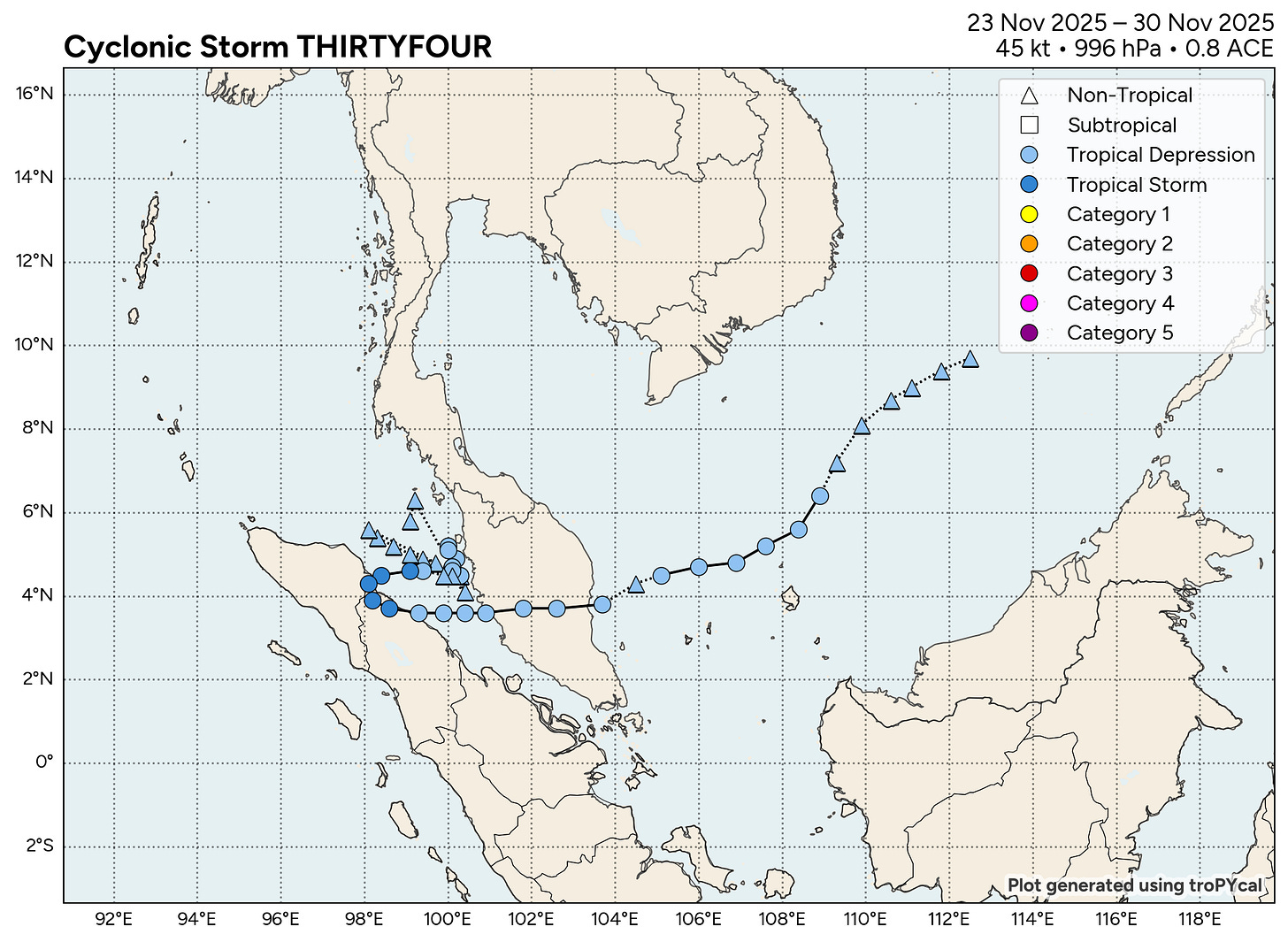

Before I get into the Atlantic recap, I want to talk about catastrophic impacts that have been occurring in other parts of the world due to tropical cyclones. Over the last week, a weak tropical system has been meandering around the region of Malaysia and Sumatra. In the middle of last week, it obtained enough organization to be designated a cyclonic storm (tropical storm) and named Senyar by the India Meteorological Department (IMD) — the World Meteorological Organization Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre (RSMC) responsible for tropical cyclone forecasting in this part of the world. Becoming a tropical storm so close to the equator — it was centered around 4N latitude — is quite unusual as the weak Coriolis force near the equator typically precludes the development of organized tropical cyclones.

Senyar in fact never became stronger than a weak tropical storm, and after a couple of days weakened back to a tropical depression. The hazard from Senyar though has been incredible rainfall totals and catastrophic flooding due to its slow, meandering movement across the region. Media reports indicate that in Sumatra more than 600 people have been killed and nearly 500 remain missing, while in nearby Thailand at least 176 people have been killed by flooding.

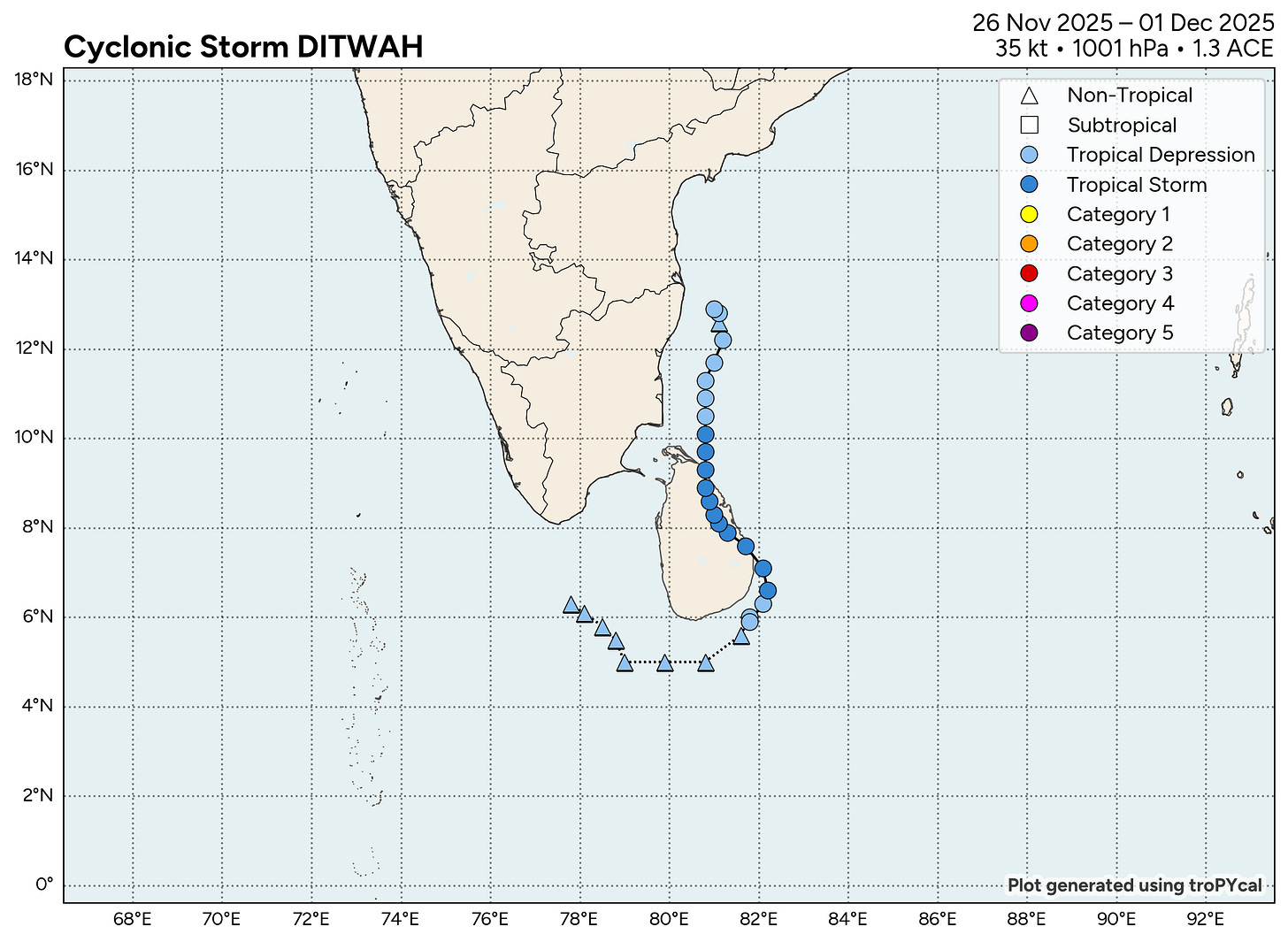

In last Monday’s newsletter, I discussed model forecasts of a tropical cyclone to form near Sri Lanka, and indeed a system formed very near the southeast coast of the island in the middle of last week. As with Senyar, this system formed rather close to the equator (around 6N) and never became stronger than a weak tropical storm, named Ditwah by IMD. Similar to Senyar, though, the slow movement of Ditwah resulted in intense rainfall and massive flooding on the island, with at least 335 people confirmed dead from flooding and hundreds more missing.

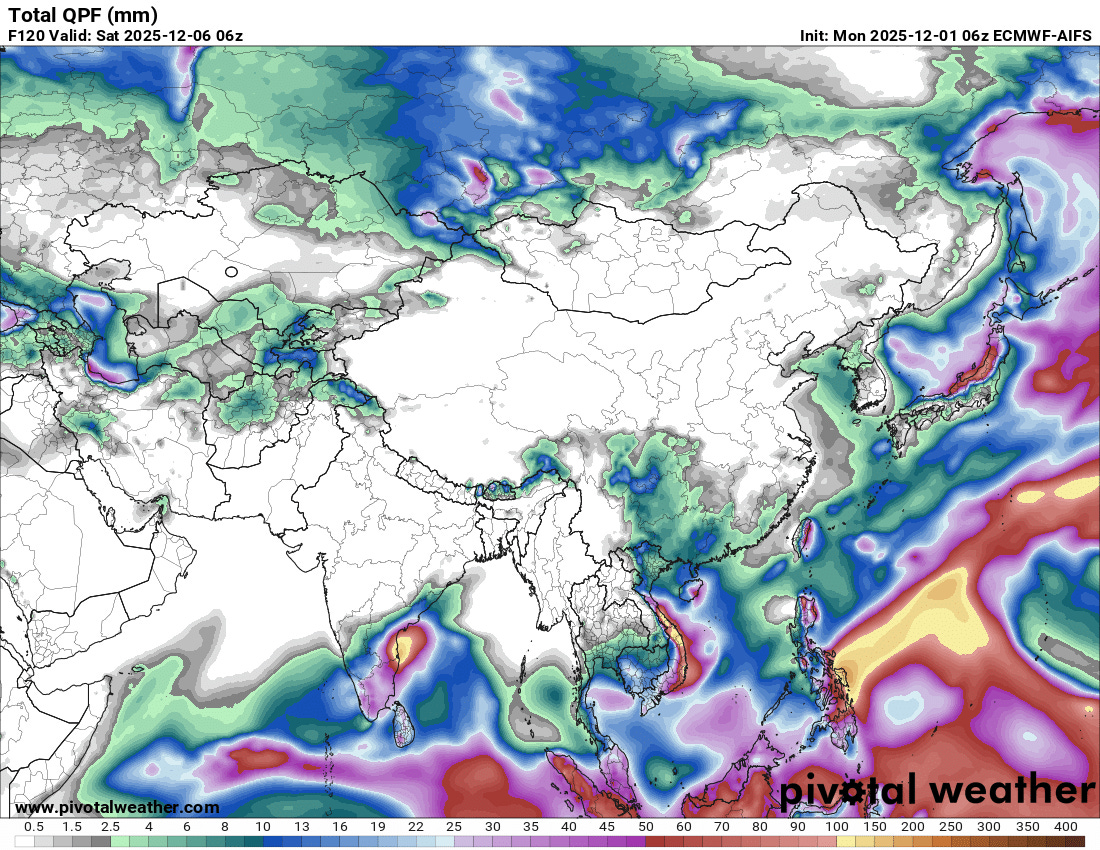

Ditwah has now moved north of Sri Lanka and is expected to cause heavy rainfall in parts of southeast India over the next several days. While the remnants of Senyar have also pulled away from Malaysia and Sumatra, additional heavy rainfall is anticipated in the region this week which could aggravate flooding and hamper aid efforts. Meanwhile, Koto has meandered off the coast of Vietnam as I discussed last week. While it is forecast to dissipate just offshore, moisture from the system is expected to produce additional heavy rainfall across the country with widespread amounts of more than 100 mm (~4”) shown in model forecasts. This could certainly cause more flooding issues in a nation that has been devastated by flooding in recent weeks.

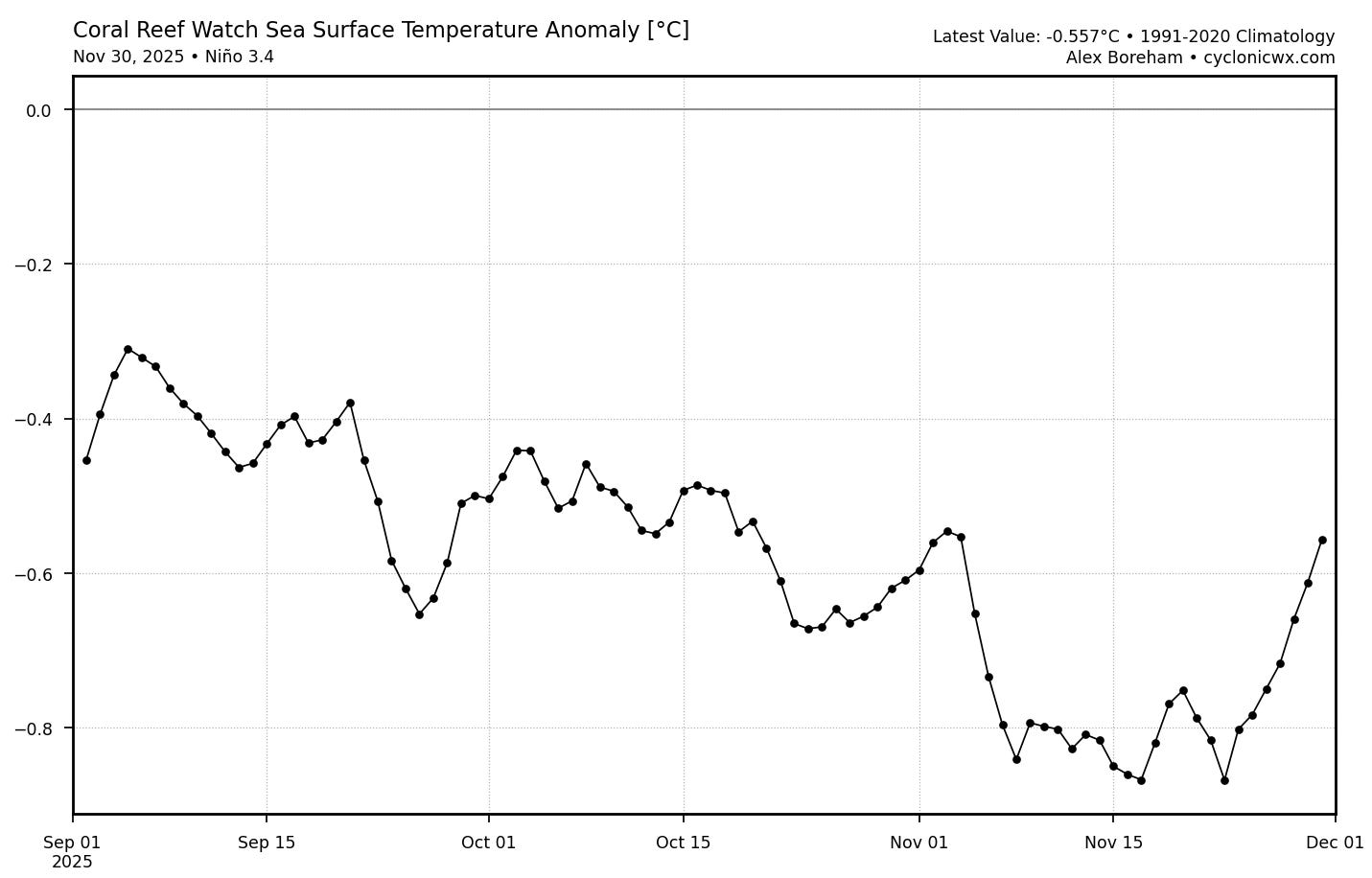

As a side note, the fact that we had two tropical cyclones so close to the equator at the same time is indicative of an ongoing westerly wind burst (WWB) in the Indian Ocean region. As noted in the Wikipedia link, a westerly wind burst is phenomenon in which the typical easterly trade winds in the equator region switch to westerly for a period of time. WWBs can promote the formation of tropical cyclones close to the equator by helping to compensate for the reduced vorticity (atmospheric spin) typically present in this region due to the weak Coriolis force.

WWB events are more typical of El Nino episodes, and as this WWB progresses east across the Pacific, it will likely have a significant detrimental effect on the ongoing La Nina. The cold anomaly in observed sea surface temperatures in the key Nino 3.4 region of the equatorial Pacific has already been weakening in the last 10 days or so as shown above, and this WWB will likely cause further warming of the equatorial Pacific in coming weeks.

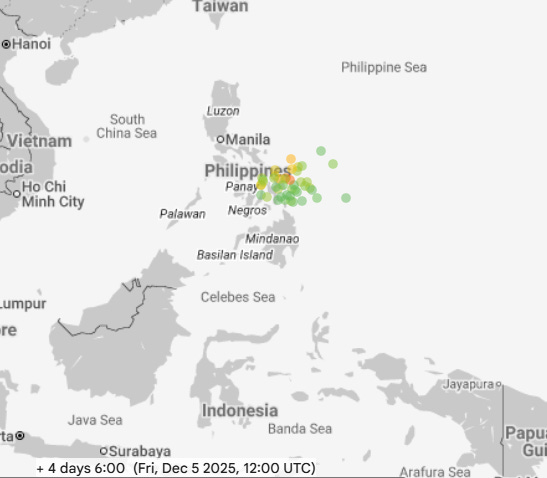

We will also be keeping an eye on the potential for a new tropical system to develop east of the Philippines and move west this week. The Google DeepMind AI ensemble (above) shows a strong tropical storm or category 1-2 typhoon approaching the central Philippines by Friday, while the European ensemble is a bit less bullish and shows more spread in the track, with some members like the GDM while others have a track farther northeast. If it were to track more to the west like the GDM shows, it could cause significant impacts in parts of the Philippines that have had serious flooding and impacts from typhoons in recent weeks, so it is definitely worth monitoring.

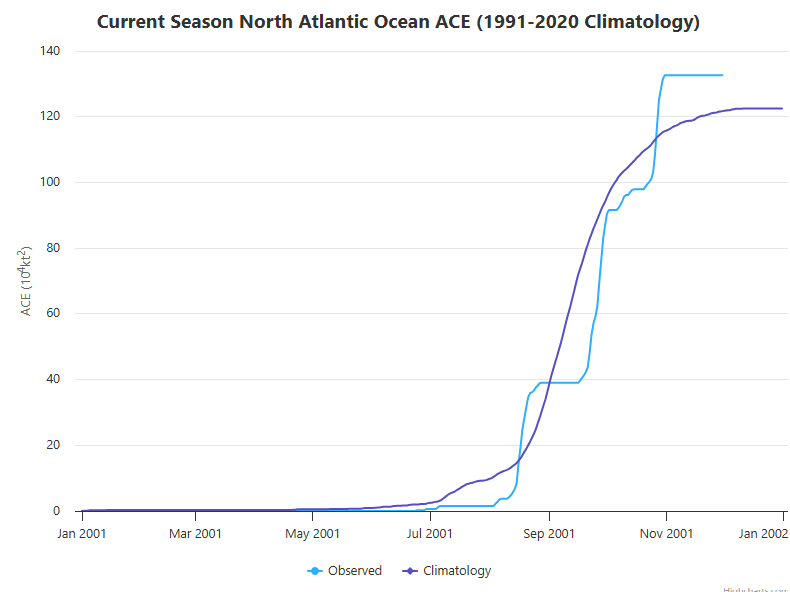

Turning now to the Atlantic, the low probability late season Caribbean system I discussed last week did not materialize, so the season essentially ended with Hurricane Melissa. As measured by accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) — the (in my opinion) best parameter for judging the overall seasonal activity as it accounts for the intensity and duration of systems instead of just numbers — the 2025 Atlantic season ended up somewhat above normal as shown above. The total 2025 ACE was 133, normal is 122.

How we got to that somewhat above normal ACE though was very unusual — indeed unprecedented. The number of named storms was also slightly above normal with 13, but most of these were relatively weak. The Atlantic only had five hurricanes, below the normal number of 7. However, four of these hurricanes became major hurricanes, and for the first time ever three — Erin, Humberto and Melissa — became category 5 hurricanes. These three hurricanes accounted for 70% of the season’s accumulated energy, and if you add in Gabrielle which reached category 4 intensity, 85% of this season’s above normal ACE is accounted for in just four systems.

For the first time since 2015, the US was spared any direct landfalling hurricanes. The only landfalling tropical storm was Chantal, which made landfall in the Carolinas in early July, causing significant flash flooding. Moisture from the remnants of Tropical Storm Barry played an important role in the catastrophic flash flooding that occurred in the Texas Hill Country on July 4-5.

In the end, I think the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season will be remembered for Melissa and its devastating impacts on Jamaica, as well as the unprecedented pattern of development with three category 5 hurricanes but almost a complete dearth of activity in the climatological peak of the season from late August through mid September. If you want a deeper dive into all of the various statistics and contributing factors to this year’s hurricane season, I highly recommend this post from tropical meteorologist Michael Lowry.

Leave a comment