Looking at how federal science and water agencies work together in flood events. Also – flood risk continue in the Pacific Northwest while the rest of the country warms up.

Dec 16, 2025

Good morning, I want to start today’s newsletter by taking a deeper look at the story about the Skagit River in Washington state I highlighted in my updated post last night. Rather than being a story about an erroneous forecast as I first described it yesterday, it now seems clear that this is a success story about how forecasts and warnings can save lives and property. Given the background context of the actual and proposed cuts to federal science and water agencies (not to mention the fact that I completely misunderstood it initially), I think this is a particularly important story to explore right now.

I want to preface this by saying that the details are still a bit unclear at this point, and I am filling in some gaps based on my own experience with hydrologic operations and collaborations. Obviously, if and when details emerge that would provide further clarification about these details, I will pass them along.

Going back nearly a week ago to the morning of Wednesday, December 10th, western Washington was facing an increasingly dire flooding threat. As I discussed in my post that morning, rivers were on the rise from multiples days of heavy rainfall, and another 24 hours of heavy rainfall was forecast in the Cascades Range which would push the levels of a number of rivers in that region into record territory.

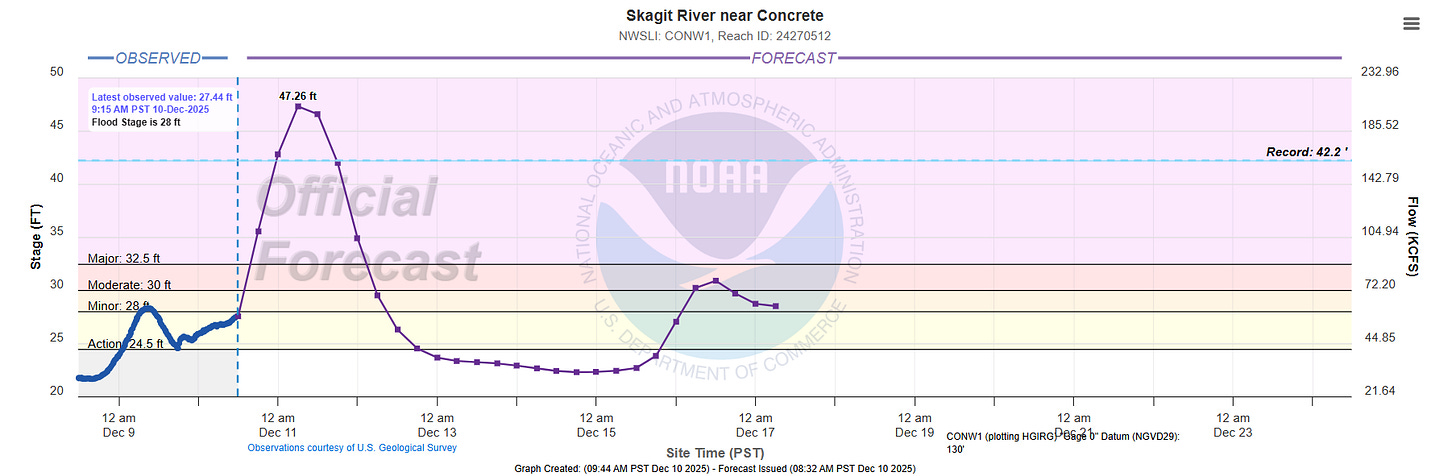

Of particular concern was the Skagit River north of Seattle, which was forecast by the NWS to shatter its all-time record stage. The above forecast for the gage at Concrete from that morning showed the river cresting at 47.26’, more than 5’ above the record of 42.2’ set in 1990. Similar levels were forecast at the downstream gage site at Mount Vernon, a city of 35K people along the Skagit.

It is important to understand just how unprecedented this magnitude of flooding would have been. Stage records on the Skagit go back at least 100 years, and the river level at Concrete has only reached 40’ five times in that period. On the river gage graph above, the left y-axis is the stage in feet, and the right axis is the flow (discharge) of the river in cubic feet per second (cfs). Flow is a measure of the actual volume in the river, and there is a direct relationship between stage and flow. The flow needed for the record stage at Concrete is about 150K cfs. To get the river up another 5 feet to the crest forecasted here, the flow would have to increase to more than 200K cfs, i.e., about a 33% increase in flow. This is a massive amount of additional runoff needed, and shows how much water was in the system due to the series of unusually wet and warm storm systems in the region.

The Skagit River and the flow into the river from its tributaries is mostly unregulated, but there are some dams that do control some of the flow. Of particular import here is Ross Dam, a large dam that is located on the upper Skagit as shown in the map above. Ross Dam is a large hydroelectric dam owned by Seattle City Light, and as a hydroelectric dam the river is generally allowed to flow through it to generate power. However, in flood situations, the city of Seattle has an agreement with the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to enable the Corps to operate Ross Dam for flood control measures.

Given the forecasts for record flooding, this contingency was activated and on December 8th the USACE began operating Ross Dam. Per a press release from USACE, flow into Ross Lake — the reservoir impounded behind Ross Dam — peaked at approximate 50K cfs during the day on December 11. In response, outflows from the dam were reduced by USACE to the absolute minimum possible (450 cfs), meaning the dam was holding back 99% of the flow down the upper Skagit.

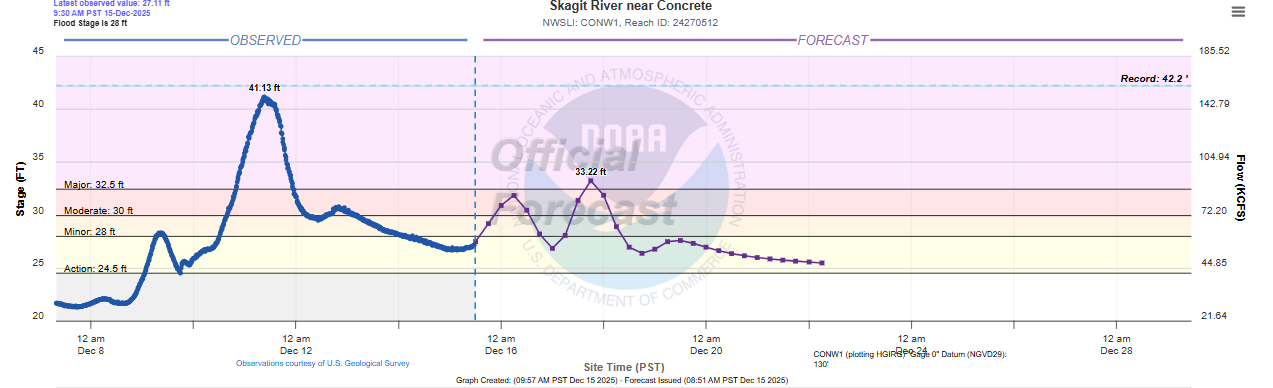

On the night of the 11th, the Skagit crested at Concrete at 41.13 feet (above), just below the record and nearly 6 feet below the forecast issued earlier that day. This means the forecast flow at Concrete ended up about 50-60 Kcfs lower than originally anticipated. It seems pretty clear that the ability of the USACE to hold the 50K cfs of flow coming down the upper Skagit into Ross Lake was the major reason why the river levels did not get as high as originally anticipated — and that this mitigation activity greatly reduced the flooding downstream, likely saving millions of dollars in property along the lower Skagit.

The complexity of this sort of operation should not be underestimated. All of that water being held back by Ross Dam accumulates and raises the level of the lake, and obviously that capacity to hold water is limited. It is crucial that USACE have accurate forecasts of river flow and future rainfall to know how much water they can safely impound. Furthermore, the long range weather forecast was key in this situation, as the heavy rainfall event now occurring in the region meant that the USACE wanted to start releasing water from the dam as quickly as possible to try to build up capacity to be able to hold additional water from the flooding event occurring today.

Again, this effort likely reduced the level of last week’s flood by several feet and saved millions of dollars in property — not to mention preventing the associated heartbreak that such losses would have produced. An operation like this does not happen by accident. It requires accurate weather and river forecasts from the National Weather Service, and close collaboration between all of the agencies involved including the NWS, USACE, emergency management and the utility companies. That collaboration is able to happen effectively during a crisis like this because of relationships that are intentionally built over the years to ensure readiness to handle such an event.

Furthermore, being able to execute this sort of a mitigation effort requires the forecasting and observational foundation of all of the federal agencies involved, including the NWS, USACE and the US Geological Survey. Erosion of the capacities of these agencies such as we have seen in the past year jeopardize our societal ability to protect communities from weather and water events such as this flood. Hopefully those in control of the budgets and staffing of these agencies will recognize this reality and act accordingly.

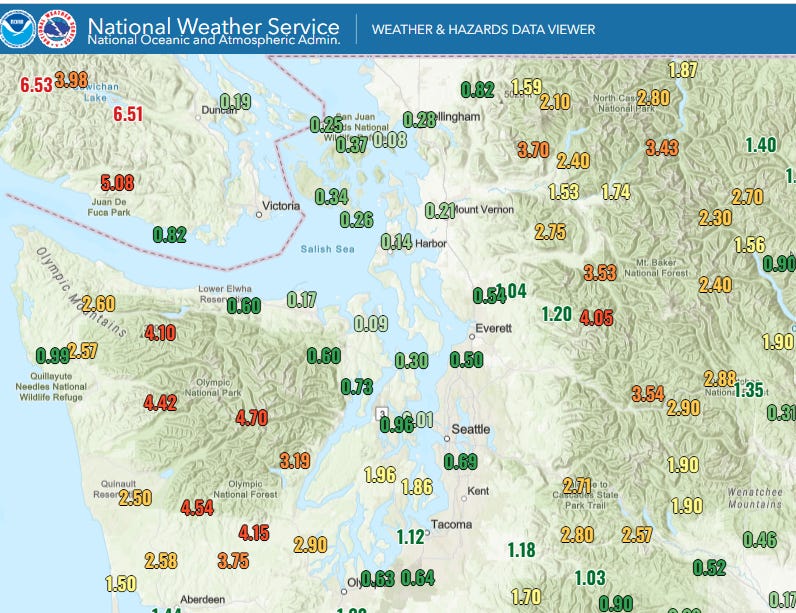

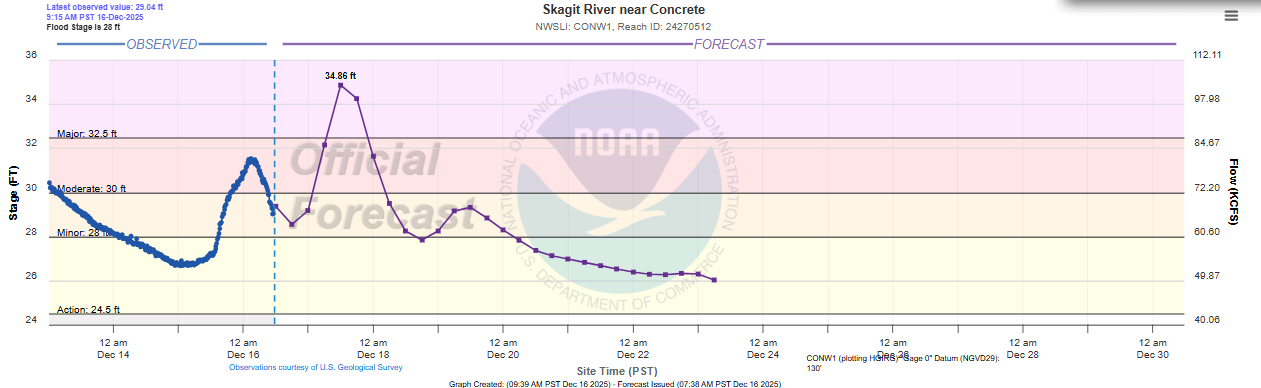

Turning to the current heavy rain and flood event in the Northwest, heavy rainfall has again been occurring in the Olympic and Cascade ranges, with 36 hour rainfall totals shown above.

This is driving river levels back up again. While not as extreme as last week, many rivers are back into moderate flood, and the Skagit River is again forecast to reach major flood levels. The USACE is again operating some of the dams on the river to try to minimize the flooding impacts. Levee breaches have resulted in some flash flooding and additional evacuations along some rivers, and numerous roads are closed due to flooding in the western Washington region.

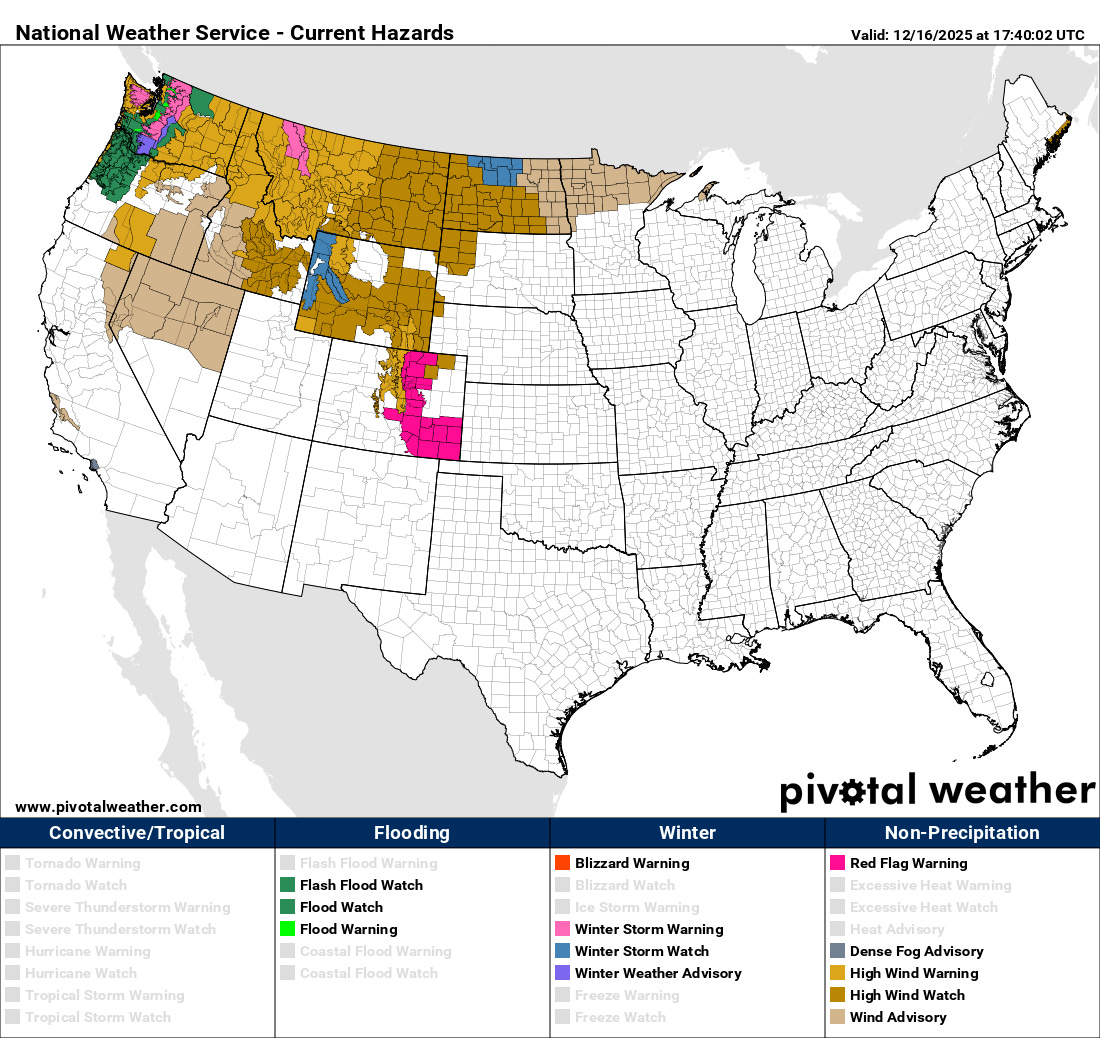

Additional heavy rainfall is anticipated in western Washington today, and flood watches continue in effect for the region. The storm systems responsible for this heavy rainfall are also producing strong winds across much of the northwestern quarter of the country, and wind advisories and high wind warnings are in effect for many areas.

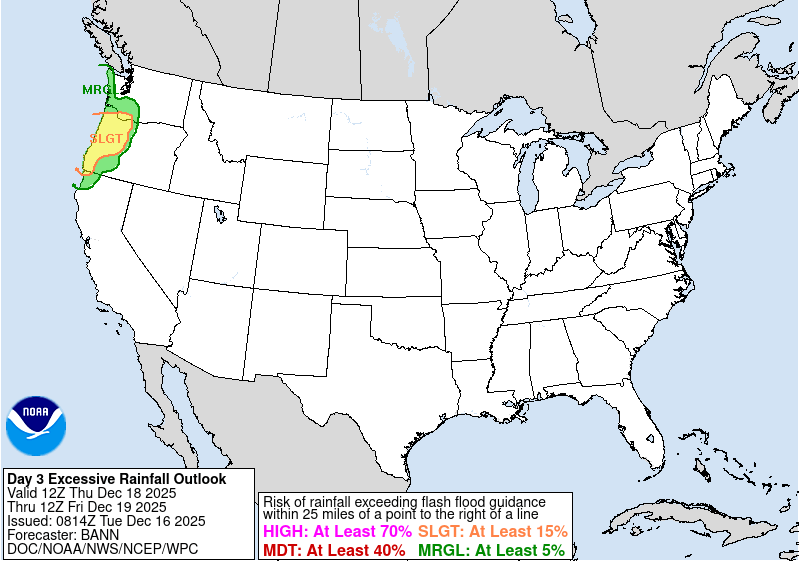

While rain will gradually diminish over western Washington on Wednesday, the next in the series of storm systems will impact the Northwest on Thursday, with the focus of heavy rainfall this time a bit farther south over western Oregon. Once again, this looks to be a warm system with unusually high snow levels, so a rather significant flood risk is likely to evolve given that much of this area has already seen above normal rainfall over the last couple of weeks and streamflows are already high.

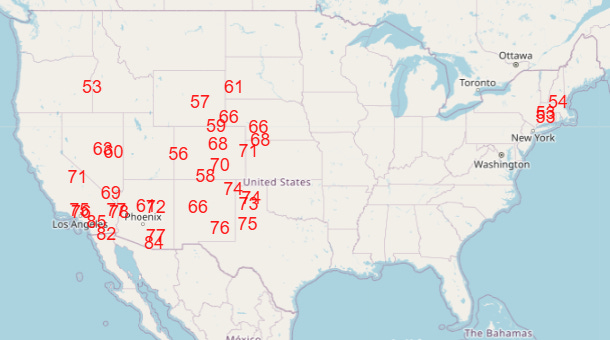

For the rest of the country, unseasonable warmth will become the dominant weather story, with record high temperatures expected to be widespread over the western half of the country by Friday. Record warmth will also be possible in the Northeast ahead of a cold front which will bring another brief shot of colder air to the eastern half of the country late this week. All signs continue to indicate an unseasonably warm Christmas week for nearly all of the country, except possibly parts of the Northeast.

Leave a comment