Looking at the pros and cons of Wireless Emergency Alerts during the nighttime hours

Jan 02, 2026

Happy New Year’s! As I mentioned a couple of days ago, I am visiting family for the New Year’s weekend, so my posting will be intermittent for the next several days. However, I wanted to make at least a short post about a situation that I have seen being talked about in the weather and alerting communities over the last day or so.

A well-organized band of snow squalls moved across parts of the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic during the evening hours of New Year’s Eve and into the early morning hours of New Year’s Day. This band of snow squalls produced strong wind gusts and a quick burst of very heavy snow that rapidly lowered visibility for a short period of time.

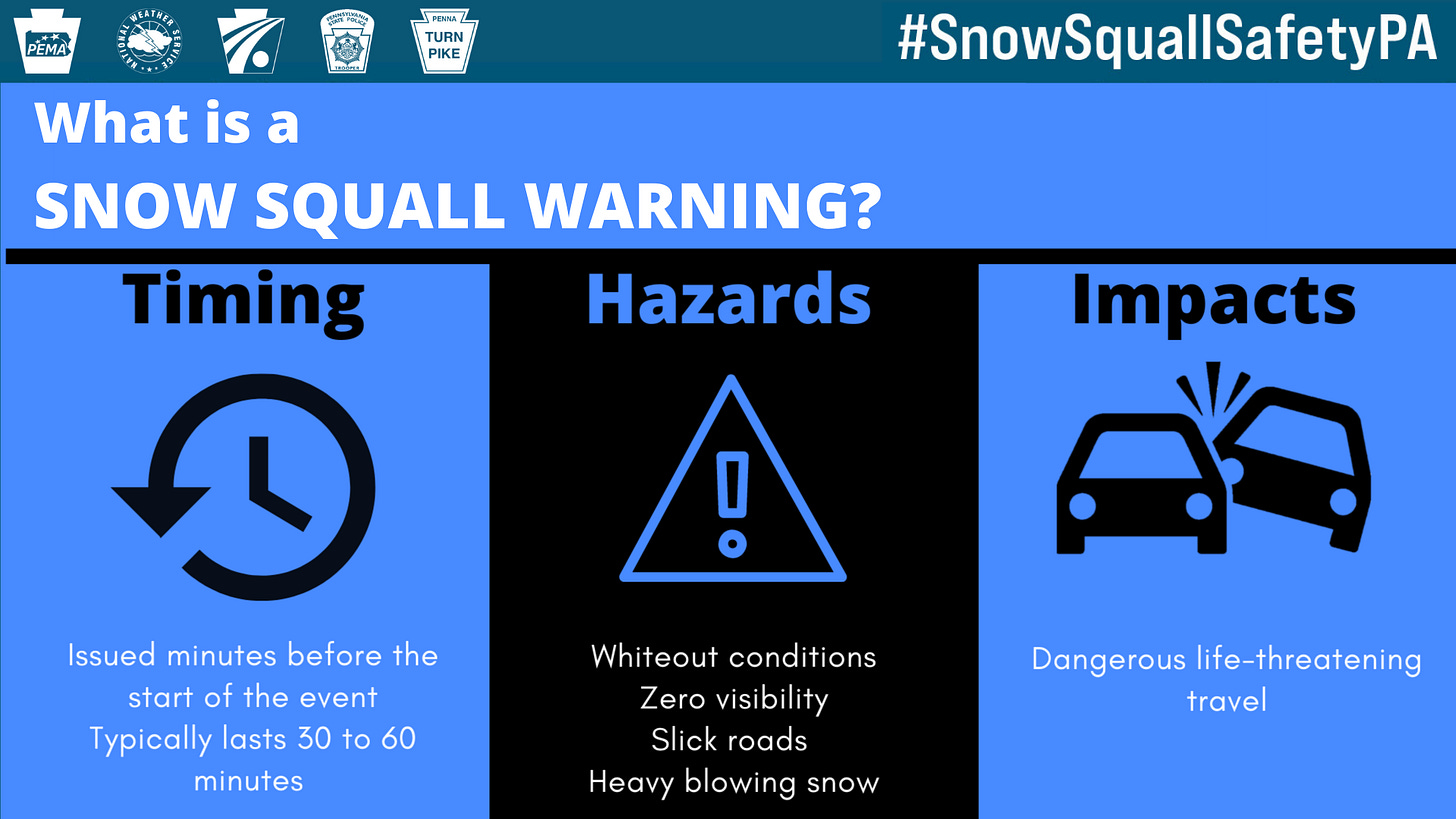

These types of events can cause serious impacts to travel due to the sudden onset of wind and poor visibility, and have been the cause of a number of large scale chain-reaction traffic incidents over the years that have resulted in numerous casualties. To try to better warn the public about these hazardous events, several years ago the NWS started issuing snow squall warnings in these situations.

Snow squall warnings are similar to severe thunderstorm warnings in that they are “short-fused” warnings, issued for 30 to 60 minutes based on radar and observations. When the NWS first start issuing these warnings, they all triggered the Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) system, meaning they activated all cell phones within the warning polygon. However, the NWS received quite a bit of feedback that there were too many alerts being generated, so starting in the winter of 2023-2024, impact based warnings were implemented.

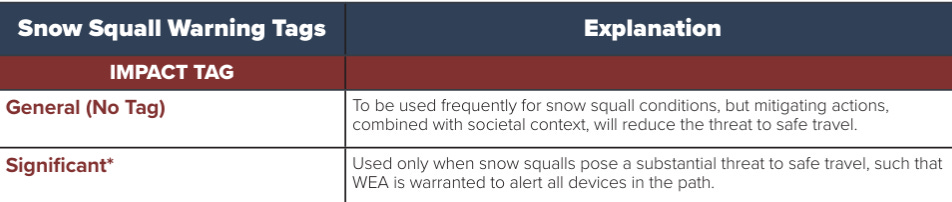

This enabled the NWS to issue “general” snow squall warnings that would not activate WEA, and “significant” tagged warnings that would activate WEA. As you can see in the table from the NWS impact-based snow squall fact sheet, the main difference in the issuance criteria is that the NWS forecaster thinks that the snow squalls pose such a threat to safe travel that “WEA is warranted to alert all devices in the path.”

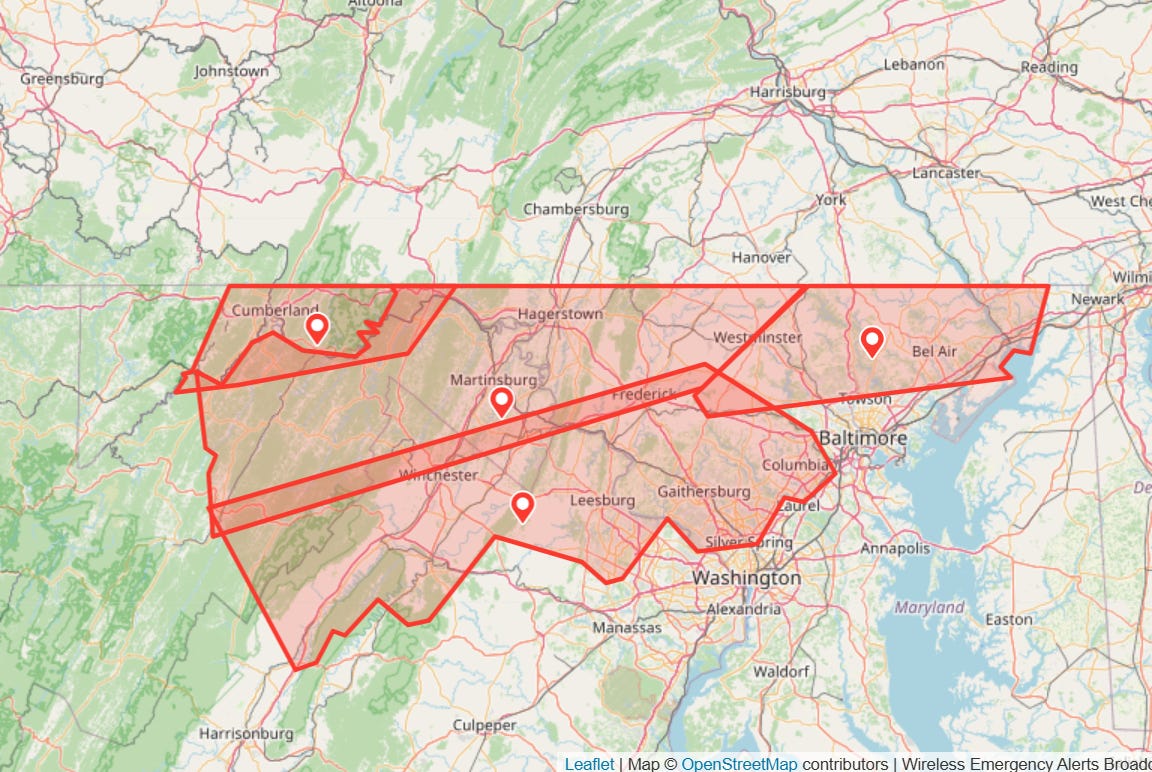

A number of snow squall warnings were issued along this band of squalls as it moved southeast from the Great Lakes to off the Mid-Atlantic coast. However, all of these were “general” snow squall warnings until the band got into the service area of the NWS Baltimore/Washington office. This office issued several “significant” snow squall warnings starting about 2:30 am as shown in the PBS Warn map of WEA activations from Thursday morning. It included two in the 4 to 5 am hour that included parts of the Baltimore-Washington urban corridor – resulting in many people getting cell phone alerts in the pre-dawn hours of New Year’s Day.

Not surprisingly, this resulted in a fair amount of media coverage, social media traffic from the public, and associated conversation in the weather and alerting social media world. The Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang made a Facebook post Thursday afternoon about the alerts, and over 350 people commented. As you might expect, the comments varied greatly – with many people expressing support for the alerts as a way of keeping people safe, while others expressed concerns about overwarning and being awakened for a threat that would only affect them if they were driving.

The NWS’ own impact-based warning fact sheet would seem to imply that snow squall warnings at this time of night should generally not be tagged for WEA triggering:

Public perception is that the NWS over-alerts SQWs and overuses WEA. This change ensures WEA activation is reserved for high-impact events. The NWS has noted a need to issue SQWs at night without triggering WEA.

Obviously, the warnings issued in the 4 to 5 am time period were in the time when early morning commuters might be starting to get on the road — but of course this consideration is complicated by the fact that it was New Year’s Day, and most people are off work.

Hopefully, this discussion helps you recognize the incredible complexity that faces a NWS forecaster when making these sorts of decisions about when and how to warn. The truth is that most meteorologists do not have the education or background to truly understand the societal factors that surround alerting, which is why social science and emergency management have become a growing aspect of the meteorological community in general and the NWS in particular.

What strikes me about this particular situation is a sense that the NWS needs clearer definitions and guidelines for what constitutes a “significant” snow squall based on collaborations with social scientists and emergency management professionals. Perhaps there is internal warning criteria provided by NWS national or regional headquarters for when to issue a “significant” warning, but the NWS directive — the official NWS policy documents— for snow squall warnings use the same differentiation criteria for “general” versus “significant” as the graphic I have above. While I certainly think it is important that the NWS forecast staff on duty dealing with events like this have some flexibility on when to trigger WEA based on the specific meteorological and societal situation they are facing, it does seem like it would behoove NWS forecasters, NWS partners, and the public to have clearer criteria for what warrants the “significant” snow squall warning issuance.

WEA alerts and the potential for overwarning obviously goes well beyond snow squalls to include the other weather hazards it is used for (primarily tornadoes, severe thunderstorms and flash floods) as well as all of the other ways in which cell phone alerts can be generated (AMBER alerts, local and state emergency management alerts, etc.) I touched on a number of these issues in a recent post about the Washington state floods in December. I would be very interested to hear from Balanced Weather readers about your experience with cell phone alerts and your perspectives on this topic. I have opened up comments for everyone for this specific post.

Leave a comment