A look at the Enderlin, ND tornado

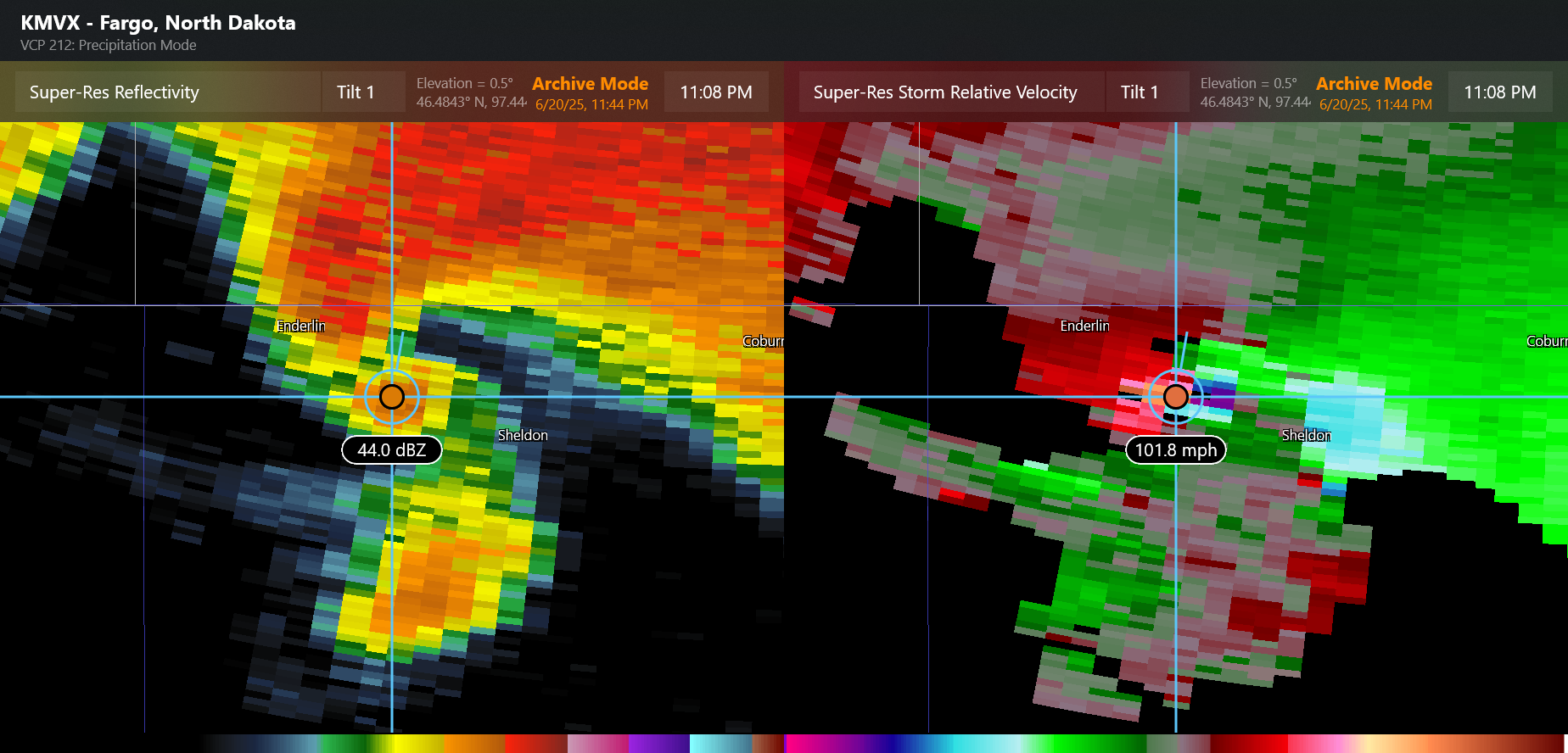

For those of you that follow me on BlueSky, you saw me post extensively Friday night and over the weekend about the severe weather late Friday in North Dakota, and how impressive it was to me meteorologically. One of the intense events that evening was the tornado that occurred shortly after 11 pm CT just southeast of Enderlin, ND. The above radar image is from 11:08 pm, close to when the tornado was likely at its most intense. The Grand Forks WSR-88D (NWS Doppler radar) detected 122 mph inbound winds adjacent to 102 mph outbound winds within the circulation associated with the tornado. This yields a gate-to-gate rotational velocity value – the difference between inbound and outbound velocity divided by 2 – of 92 knots (106 mph), which is an upper echelon value for this parameter.

NWS forecasters can issue three levels of tornado warnings: base (standard) warning, considerable (particularly dangerous situation), and catastrophic (tornado emergency). The NWS Warning Decision Training Division has impact-based tornado warning decision guidance that enables forecasters to develop a real-time probabilistic estimate of a tornado’s intensity based on the rotational velocity and the significant tornado parameter (STP) to help decide which level of warning to use. STP is an environmental parameter that combines atmospheric instability and wind shear to provide a meteorologist with a quick estimate of how favorable the environment is to produce significant (EF2+) tornadoes in a given region. The chart above is valid at 11 pm CT, and shows values greater than 9 over southeast North Dakota. The combination of rotational velocity and STP for the Enderlin tornado is at the top of the categories and would support the use of a catastrophic warning for a potentially violent tornado.

Another tool that meteorologists use in the tornado warning process is the dual-polarization radar product correlation coefficient (CC). This product essentially gives the meteorologist information about the size and shape of the particles being detected by the radar. When values of CC are low and collocated with the other signatures of a tornado, they indicate the presence of debris being lofted by a tornado. In the Enderlin event, a large debris signature was detected by the radar that extended well above 10,000 feet, another indication of an intense tornado.

Given all of this radar data, it was of course no surprise when the morning brought pictures of significant damage from this area. I highly encourage you to watch this YouTube video that provides an aerial tour of the damage. Unfortunately, 3 people lost their lives in this tornado, making it the deadliest tornado in North Dakota since 1978.

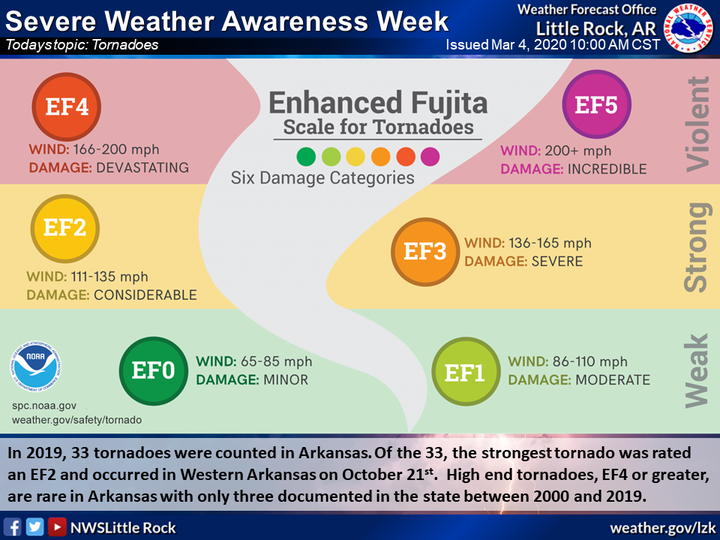

The NWS in Grand Forks surveyed the damage produced by this and several other tornadoes that occurred Friday night in their area. They have rated this tornado a high end EF3 on the Enhanced Fujita scale with maximum estimated winds of 160 mph.

Tornadoes are categorized as weak (EF0/EF1), strong (EF2/EF3) or violent (EF4/EF5); prior to the implementation of the Enhanced Fujita scale in 2007, they were categorized in the same manner on the Fujita Scale.

As you can see in this graphic from The Weather Channel based on SPC data, violent tornadoes are the rarest, accounting for just about 0.5% of all tornadoes. Having pointed out the rarity of a violent tornado, I still admit to being a bit surprised given the pictured damage and radar presentation that the Enderlin tornado was not violent – but obviously I was not on the ground doing the survey and do not want to second-guess what the NWS meteorologists onsite were able to see and evaluate in the damage. However, as I rewatch the damage video I shared above, I cannot help but think about my conversation a few weeks ago with NSSL scientist Dr. Tony Lyza about the tornado damage scales and possible inconsistencies in the tornado record. My sense is that this tornado provides a clear example for some of the concerns he talked about.

One of the most incredible sights from this tornado was a train that was derailed by the tornado. Not only was the train derailed, but one of the cars was moved nearly 100 yards as seen in this picture and per the NWS damage survey. The current Enhanced Fujita scale does not use vehicles as a damage indicator – but under the old Fujita scale damage to vehicles was one of the key indicators used. For an F4 tornado, the Fujita scale reads:

Whole frame houses leveled, leaving piles of debris; steel structures badly damaged; trees debarked by small flying debris; cars and trains thrown some distances or rolled considerable distances; large missiles generated.

Obviously, what we see in the picture above matches very clearly the last part of the F4 damage descriptor. In fact, when you watch other parts of the damage video, you can see damage that correlates well with the “whole frame houses leveled, leaving piles of debris” and “trees debarked by small flying debris.” Again, my point here is not to second-guess the official rating, which is done based on the EF scale damage indicators, but rather to show how this tornado might have been rated in the pre-EF scale period. As someone who rated dozens of tornadoes using the old Fujita scale, it is hard for me to imagine that this tornado would not have been rated as F4, meaning it would have been categorized as a violent tornado.

If you have any interest in tornado damage rating or the climatology of tornadoes, I highly encourage you to go back and watch my video with Tony and listen to his commentary in the context of this tornado, and how more recent tornado ratings may be skewed toward strong tornado ratings and away from the violent category of tornadoes. As a scientist who has been involved in tornado research and warning operations for decades, I am very invested in the importance of an accurate, consistent tornado climatology, and hope that our community can work through some of the potential issues that the work of Tony and his colleagues are bringing to light.

I hope you have found this deep dive into the Enderlin tornado interesting and educational. I would love to hear any questions or comments readers might have and have opened up the comments to all subscribers. If you are finding Balanced Weather to be interesting or helpful, I hope you will consider subscribing. As a retired NOAA meteorologist, I am hoping to make Balanced Weather an ongoing project to help provide science based weather information like this – as well as ongoing coverage and commentary on the current threats facing science in general and weather and earth science in particular. Every paid subscription helps me be able to dedicate more time and effort to this Substack. You can also subscribe to the Balanced Weather YouTube channel where my interview with Dr. Lyza resides along with several other videos; I will be adding more content to that site in the coming weeks and months.

Leave a comment