Many questions raised about local officials and emergency management

Aug 01, 2025

I was busy monitoring weather yesterday and am just now catching up on the various media reports summarizing yesterday’s Texas legislature investigative hearing about the Texas Hill Country floods in early July. I wrote a recent deep dive into the Guadalupe River flood event after the initial hearing in Austin last week, but I feel compelled to share some additional thoughts and reemphasize some points based on articles about yesterday’s hearing and some feedback I received after my initial article.

I want to start with this article from NPR, and the comment off the top that “the flood was sudden, and officials have agreed it was unpredicted.” I agree that the flood was sudden and unpredicted if we are talking about the day before, and I wrote in my article earlier this week about ways in which I think the NWS could have potentially improved their messaging the evening before the event and strategies that might help better communicate flash flood risks in future events.

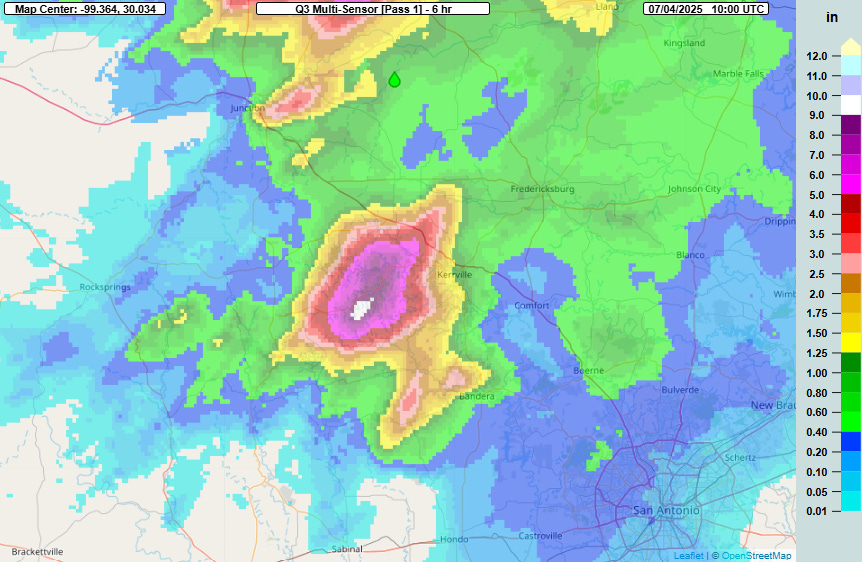

However, anytime a point is made about the “unpredictability” of this event, it needs to be stressed that at a fundamental level a catastrophic flash flood is almost always going to be sudden and unpredictable. Flash floods like this and other historical catastrophic flash floods with large numbers of fatalities such as the 1972 Black Hills flash flood and 1976 Big Thompson Canyon flood are the result of intense, localized rainfall in the precise spot necessary to generate a massive flood wave. The above 6-hour MRMS rainfall from 5 am that morning shows the relatively localized rainfall of 6-10” in just a few hours in the exact area needed to generate the massive floodwave that devastated the region along the Guadalupe River. Bottom line: the state of hydrometeorological science is not such that we can tell you with any significant lead time precisely how much rain will fall and if it will fall in the exact right location to produce a devastating flash flood. This is why it is so critical to have multiple ways of receiving a flash flood warning if you are in the flash flood prone area: the warning might be the first indication you have of potential danger, especially given that in some flash floods the rainfall producing the flood can occur upstream from you and you may be completely unaware that it even fell.

This takes us to the warning phase of the Guadalupe River flash flood and the scrutiny that local officials have come under for their lack of awareness and action while the event was unfolding. This Houston Chronicle article focuses on this aspect of the testimony at yesterday’s hearing. Yesterday’s testimony conclusively shows that the three main officials responsible for public safety in an event like this in Kerr County, namely the county judge, the sheriff, and the emergency manager, were asleep or otherwise unavailable during the most critical time of the the flash flood event.

While those facts were made clear, a number of other questions were raised by the testimony from these three officials. According to the sheriff, the county became aware of the unfolding magnitude of the flash flood at 3:34 am and that it was an “all-hands on deck” situation when a call was received from a family on the roof of their home, asking for air rescue. However, he also stated that he was not contacted until nearly an hour later at 4:20 am, which seems inexplicable given the gravity of that call at 3:34 am. Meanwhile, the emergency manager was not contacted until 5:30 am when he received a request from a the city of Kerrville to respond to the flood.

As you might expect, legislators were not happy about these revelations. From the Houston Chronicle article:

“The three guys in Kerr County who were responsible for sounding the alarm were effectively unavailable. Am I hearing that right?” asked state Rep. Ann Johnson, D-Houston. She pointed out that as early as 2 a.m., according to reports she’d heard, “there were little girls with water around their feet” at Camp Mystic on the Guadalupe River.

Twenty-five campers, two counselors and the camp’s leader, Dick Eastland, died in the disaster.

“Is there a protocol that needs to be put in place?” Johnson asked. “That, if the three folks who are responsible at this moment are not available for whatever reason, what should we do?”

“Yes ma’am, we can look at it real hard,” Leitha (Kerr County sheriff Larry Leitha) responded. “Maybe they can call me earlier.”

I have to be honest, reading this leaves me physically shaken and emotional. Yes, there is a “protocol that needs to be put in place:” it’s called emergency management. In the testimony from county officials yesterday, they stressed that they are a rural county with limited resources that has to deal with large influxes of seasonal visitors. I am certainly sensitive to that. However, I was meteorologist-in-charge of the NWS office in Jackson, Mississippi, and worked for more than a decade with state and local emergency managers who faced very similar challenges in a region that deals with serious weather hazards nearly year round. Through their incredible dedication and commitment to the principles of emergency management, most of them were able to develop effective emergency operations plans that ensured that they could receive and disseminate warning information and be able to quickly spin-up to respond to evolving weather and disaster situations.

Nothing that we have heard from Kerr County officials since the July 4th tragedy suggests that they had even the most basic of emergency operations plans in place, or if they did, they were completely ineffective and had not been properly exercised or evaluated. Knowing how seriously my emergency management colleagues took their responsibilities, it is completely inexplicable and maddening to me that in an area with known catastrophic flash flood potential and large numbers of people in vulnerable situations that this could be the case. The very idea that “maybe they could call me earlier” is the answer to a question about the need for better protocols after the obvious lack of basic emergency operations procedures during a catastrophe that killed more than 100 people is infuriating to me as someone with expertise in these areas.

Government entities need to have multiple, redundant ways to both receive and disseminate critical warning and alert information, as well as a clear emergency operations plan that outlines when and how to activate warning notification systems as well as the responsibilities of key officials and who their backups are when they are unavailable. All the information we have to this point suggests that none of this was in place, and if it had been, lives may have been saved just by letting people in vulnerable areas know that they needed to get to a higher location.

Clearly, the county was aware shortly after 3:30 am of the magnitude of the flooding, yet a CodeRed alert warning of flooding did not go out until after 5 am. In his testimony yesterday, Sheriff Leitha testified that the dispatchers at the 911 center were “overwhelmed” and unable to get to the alert until then. Again, I am completely sympathetic to the plight the dispatchers must have faced that night, but this is why you have clear emergency plans that are frequently tested out and have multiple redundancies to ensure critical actions are taken.

Just in the last week or so, I have on 3 different occasions had outdoor activities I was participating in halted because someone responsible for monitoring the weather at the facilities I was at determined it had become unsafe. These experiences have reinforced to me that just basic steps like having a person designated to monitor the weather can be a very effective mitigation tool. One of the parents who lost a young daughter in the flood testified that the county should have “warning systems based on the precise level of river rise, saying that sirens going off every time the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issues an alert would be ignored.” I certainly agree with this, but we first need to make sure basic emergency preparedness steps are taken. Simply installing some streamflow gages higher up both the north and south forks of the Guadalupe would give the National Weather Service and county officials immensely better information on the magnitude of building floods; combined with more robust emergency planning, this could provide much more timely and effective warning information to people in vulnerable locations along the river.

Since I first published my “Row Away from the Rocks” article on Tuesday, I have received a number of comments about various aspects of this event, ranging from whether the NWS could or should have issued the flash flood emergency sooner to the efficacy of NOAA Weather Radio given that it can only alert at a county level. These are fair questions, and there are obviously a lot more questions and aspects that need to be examined than I can dive into in a single article. I hope to address some of these more detailed questions in future posts.

Another comment I received brings me to my final point for today. It was suggested to me that we should not shy away from assigning “blame,” essentially from the perspective that doing so is an important part of having accountability and learning from an event so we can be better. I overall agree, but the reason why I do not want to “assign blame” is that I do not believe that should be done by a single person. I hope that by writing these posts that I am sharing somewhat unique perspective as someone who has extensive experience in both meteorology and emergency management. However, what is truly needed not only for this event but for all disasters is an impartial entity similar to the National Transportation Safety Board that can dispassionately examine these tragedies at a deep level from both physical and social science perspectives. This is an idea that has been gaining traction as discussed in this NBC News article by Evan Bush, and I hope that it will become a reality in the not too distant future. The only way we prevent future tragedies is to learn from them when they happen. The incredible safety record of commercial aviation in this country in the last few decades is a testament to the success of the NTSB approach, and I truly believe a similar concept would be a massively positive step for improving how our society predicts, prepares for and recovers from natural hazard events.

Leave a comment