When a federal government “shutdown” is not really a shutdown. And also looking at the continued longer term impacts of ongoing and threatened budget cuts.

Happy Halloween! After Melissa gave Bermuda a glancing blow overnight — winds gusted to hurricane force on the island but overall the worst passed west of them — it has become a powerful post-tropical storm system over the north Atlantic. It will pass close enough to Newfoundland tomorrow to enhance ongoing impacts from a nor’easter.

While that nor’easter and another system will continue to provide some wind and precipitation to the Great Lakes and Northeast, and some rain and mountain snow will move into the Pacific Northwest ahead of a storm system, overall rather quiet weather is expected nationwide on this Halloween. With that, I want to focus today’s post on an important Melissa-related topic that I want to talk about before that event gets too far in the rear view mirror, namely the actual and potential impacts on NOAA and the broader federal science and response community during Melissa from government cutbacks and the ongoing government shutdown.

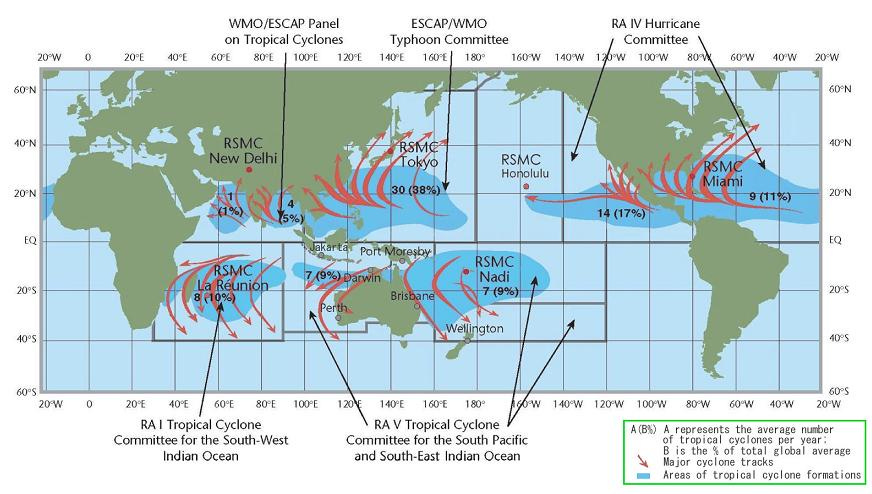

I want to start this off by reminding everyone that even though Melissa did not directly impact the United States, the National Hurricane Center serves as the World Meteorological Organization’s Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre (RSMC) with responsibility for providing tropical cyclone forecast services for all of the Atlantic and eastern Pacific. This means our nation volunteered to be responsible for providing this critical, life saving information to our neighbors in the Western Hemisphere. While NHC certainly has a primary responsibility to the United States, I know it thankfully takes this international role very seriously.

And of course Melissa could have very easily moved another 100 miles or so farther west than it did before it turned northeast, resulting in impacts to Florida or other parts of the East Coast. So the fact that we did not have to deal with the disastrous effects of Melissa is merely a lucky alignment of the weather pattern, and I think it is instructive to think about the current state of our federal resources in relation to Melissa.

Let’s start with the known impacts and this (in my opinion) absolutely bonkers story from Scott Dance in the New York Times describing how the Hurricane Research Division (HRD) of NOAA Research’s Atlantic and Oceanographic Marine Laboratory (AOML) has been relying on volunteers to continue critical data collection and projects that support hurricane forecasting. My summation of the article: because of the DOGE/OMB staff reductions early this year, HRD lost a significant number of federal scientists with the experience to operate the complex observational equipment on NOAA reconnaissance aircraft, and so they have been relying on those recently retired employees to volunteer to fly on reconnaissance missions this season to ensure that critical data continues to be gathered.

My initial reaction as a longtime federal supervisor is that I am amazed that “we” are allowing, and indeed relying upon, unpaid volunteers to undertake the inherent hazards of flying on a federal aircraft into a hurricane. As has been widely reported, several USAF and NOAA reconnaissance flights into Melissa experienced severe turbulence surveilling this record storm and in some cases had to abort or suspend their missions in order to inspect the aircraft for damage. The very idea that staffing reductions implemented by the administration have put my former agency in the position of either sending unpaid volunteers into this hazardous environment or not having crucial, life-saving meteorological data is absolutely appalling to me.

Even more infuriating is that even with these volunteers, the NOAA reconnaissance flight crews are undertaking these hazardous mission without an optimal number of crew members:

Because of the federal government shutdown that has now stretched on for a month, smaller-than-normal crews have been staffing NOAA’s hurricane hunter missions into Melissa for the past week, Dr. Marks said. Instead of two scientists, there is only one aboard each aircraft to oversee data collection from a Doppler radar system and observation devices, called dropsondes, that are tossed into the storm. Crews that sometimes numbered 15 to 18 now include about 10 or 11 people, Dr. Marks said.

So it’s not enough that we are relying on volunteers for these crucial, dangerous missions — we are also expecting them to do more tasks than normal on these complex missions because of staffing constraints. In my opinion, my colleague Dr. Frank Marks as well as Dr. David Atlas, the retired AOML director, made comments for this story that summarize much of what we are seeing with the federal government as we have navigated the recent staff reductions and now the shutdown.

“With the losses, we have a very young remaining staff and not a lot of experience flying in hurricanes,” Dr. Marks said. “The data’s been flowing,” Dr. Marks added, emphasizing that there has been no interruption to valuable tropical cyclone observations. “They’re doing their job.” But as Hurricane Melissa quickly strengthened to near-record intensity, creating an urgent need to capture observations of the storm’s winds and moisture as the storm approached Jamaica, “it’s been trying to say the least,” Dr. Marks said.

The lab’s hurricane research division employed 23 people and also had the support of 29 staff at NOAA-affiliated Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies at the University of Miami as of 2020, according to Robert Atlas, who retired from the NOAA lab in 2019 and serves as its director emeritus on a volunteer basis. Now, the division employs 10 people, plus 18 staff members employed at the university institute, Dr. Atlas said. “We’ve lost a substantial number of employees,” he said. “We’re still functioning, I think, pretty well — primarily because of the dedication of the employees.” (emphasis added)

Agencies like NOAA have lost hundreds of employees with thousands of years of job experience. The more inexperienced employees left behind are being asked to carry on the same level of work with insufficient staffing. However, the data continues flowing and the services keep being provided primarily because the people who take on this line of work are mostly incredibly dedicated people who would do just about anything to ensure critical mission activities continue to the public unaffected.

The stark reality is that even the actual NOAA employees on these aircraft reconnaissance missions into Melissa were essentially volunteers at this point due to the government shutdown. Obviously they “should” get paid when the shutdown is over, but if I were still a federal employee having to work because I was in excepted status, I certainly would not have a ton of confidence about when or even if that pay might arrive given the rhetoric coming out of the administration and Congress.

The shutdown is able to be used as a political tool by the executive and legislative branches because we exempt life-saving and law enforcement government activities, and dedicated employees continue to perform these services with no clear idea of when they will get paid for their work. This clearly extends beyond weather forecasting to things like air traffic control, TSA, etc., but sticking with the subject of Hurricane Melissa and weather forecasting, I want to list what would go away if we really shutdown the government, i.e., kept all NOAA employees and home and turned off all the data and websites that NOAA employees and funding keep going.

- All forecasts, warnings advisories and products from the National Weather Service, including local offices and the National Hurricane Center, Storm Prediction Center and Weather Prediction Center

- All radar data from the national Doppler weather radar network. No RadarScope, no GRLevel, no radar data for The Weather Channel, AccuWeather or broadcast meteorologists other than station owned radars.

- No NOAA computer model data, i.e., no Global Forecast System (GFS), high resolution models, etc.

- No hurricane aircraft reconnaissance data or hurricane models such as HAFS or HWRF

- No NOAA geostationary satellite data

Envision the ability of society to respond to prepare for and respond to Melissa without any of this data. And to take the exercise further, envision specifically the United States and our state and local officials’ ability to respond to a landfalling hurricane of Melissa’s intensity without any of that data. Obviously, we do have private sector capacity in the US that would help to fill that massive void to some extent, but it would still be a huge challenge.

Now, imagine all of this going missing along with the stoppage of the air traffic system due to FAA and TSA employees and systems going offline, federal law enforcement being at home, etc. I just recently flew to and from a meeting in Massachusetts and while I had some delays, the overall experience was pretty normal and in fact I was amazed at how cheerful the TSA agents at the airport in Manchester, NH were given they are working without pay. I am betting we would not be in day 31 of a “shutdown” with no end in site if the shutdown actually meant the loss of all of these services instead of the services continuing on the back of unpaid, dedicated federal servants.

Even when the shutdown ends and (hopefully) all of these federal employees who continue to work get paid, NOAA will still be facing the staffing shortages due to the DOGE/OPM cuts and longer term chronic issues. In the NYT article about the situation at HRD, a NOAA spokesperson talked about these issues:

Kim Doster, a NOAA spokeswoman, said she was not aware of any retired staff volunteering to assist agency employees but that the National Weather Service, another branch of NOAA, “remains adequately staffed to meet its mission of protecting lives and property.” The Weather Service “continues to prioritize the advancement and improvement of our models with cutting-edge data and emerging technologies,” she said in an email.

I cannot comment on her personal awareness of the retired staff working at HRD, but I can comment on the rest of it: in my opinion, it’s nonsense. The NWS has enough staffing to have so far avoided any glaring, disastrous impacts on services, again primarily because of the dedication of their employees and willingness to work a lot of overtime and double shifts (now, of course, without any idea of when or if they will get paid for it). But that is not the same as being “adequately” staffed.

Even with that said, a couple of weeks ago I talked a lot about how lack of upper air data due to NWS staffing shortages likely contributed to poorer forecasts for the catastrophic flooding in western Alaska from the remnants of Typhoon Halong, and Lauren Rosenthal did an excellent deep dive on the topic for Bloomberg as well. My meteorological colleague in Alaska Rich Thoman did a comparison of the availability of upper air data leading into a similar but well forecast event in 2022 with the remnants of Typhoon Merbok and the recent situation with Halong. He found that in the week leading up to the impacts from Merbok, 105 percent of the typical number of upper air observations were made from the six NWS upper air sites in western Alaska (Kotzebue, Nome, Bethel, King Salmon, Cold Bay and St. Paul). Conversely, in the week leading up to the impacts from Halong, only 44 percent of the normal number of upper air flights were made. Again, while quantifying the impacts would require a detailed scientific study, it seems extremely likely that this lack of data due to NWS staffing issues contributed to poorer than normal model forecasts (from all global models, not just the American model) and complicated the already challenging process of alerting and preparing residents of rural western Alaska for this devastating event.

With regard to the second part of the spokesperson’s statement that NWS “continues to prioritize the advancement and improvement of our models with cutting-edge data and emerging technologies,” I again call BS (pardon the colloquial language).

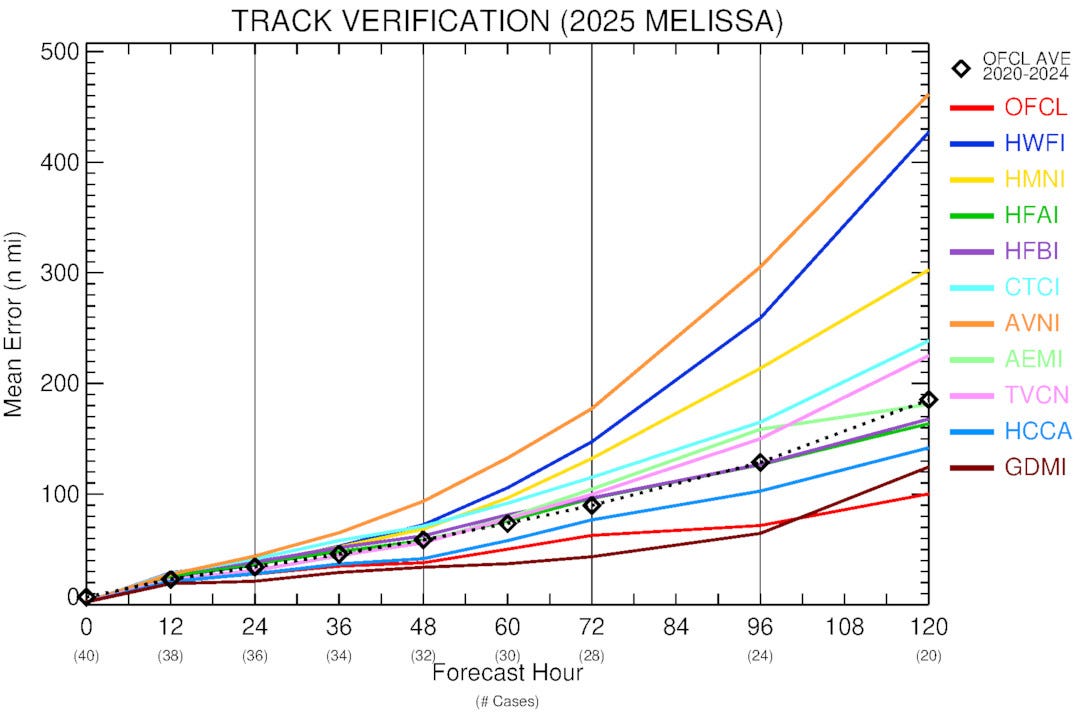

The NWS’ flagship weather model the Global Forecast System (GFS) was a notably poor performer and outlier model in the forecasts for Melissa. This verification graphic longtime hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy posted this morning on Bluesky shows that the operational deterministic GFS (AVNI in the graph) was the worst performing model for the track forecast of Melissa. The GFS ensemble forecast (AEMI) was better, but still outperformed by most model guidance, including the new Google DeepMind AI forecast system which once again had the best track forecasts.

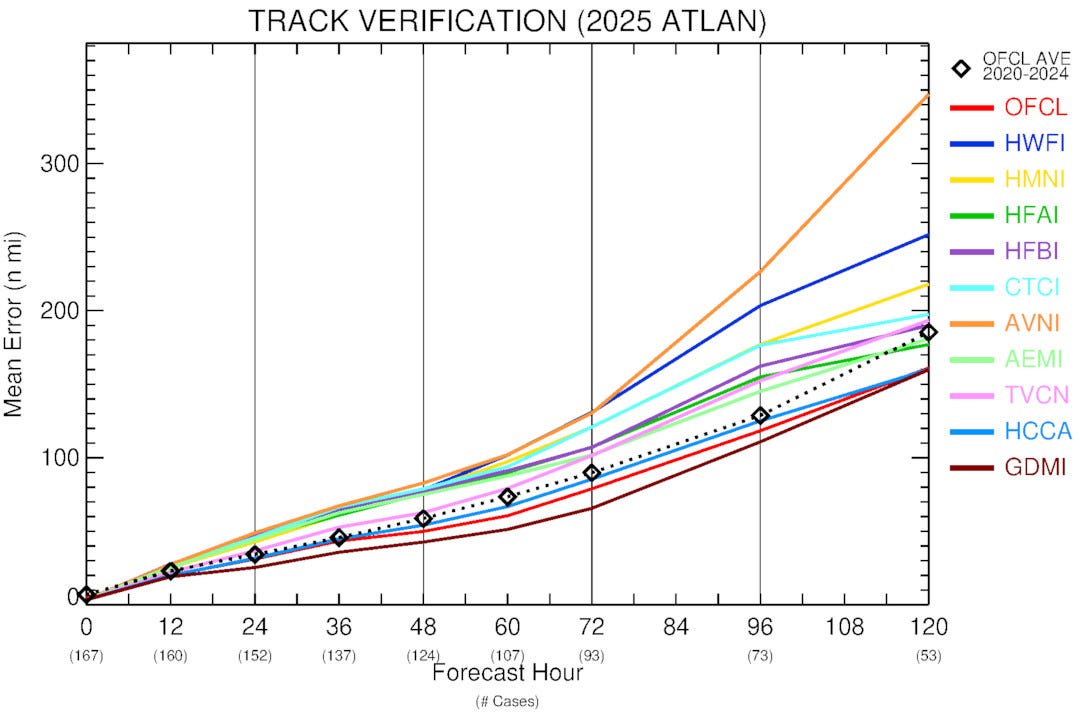

Melissa is not unusual in any sense with these struggles by the GFS. A similar graphic that Brian posted for the entire 2025 season again shows that the operational GFS ranks worst of all the model guidance. Note: these verification plots do not include statistics for individual global models such as the European Centre and UK Met Office models, but they are included within the TVCN and HCCA consensus forecasts and almost assuredly performed significantly better than the GFS based on historical performance.

Again, this is not a 2025 problem — this is a long term problem. The chronic struggles of American global numerical weather prediction (NWP) is why the Earth Prediction Innovation Center was formed, to try to provide a nexus for organized collaboration to move our global numerical weather prediction forward. I am pretty confident given the staffing shortages NOAA is facing, and the chaotic environment of the National Weather Service that former colleagues are describing to me due to those staffing shortages, that there is a keen, well organized focused effort on improving NWP right now.

Improving NWP is of course not the only challenge NOAA faces. With everything else going on I have not focused much on a report the Department of Commerce Office of Inspector General (OIG) released in July describing how NWS has been consistently failing to meet the agency’s own goals for tornado warning metrics and outlining several key steps that NOAA needs to take to improve tornado related research and warning/forecast programs. While this is obviously a very complex topic and I have my own views on it (planning a future detailed post), there is little doubt that the NWS needs a focused effort to improve their short-fused (tornado, flash flood, severe thunderstorm) warning programs, and the current staffing and budgetary state of NWS and threatened elimination of the research arm of NOAA by the administration is unlikely to make such an effort viable or effective any time soon.

As if this were not enough, of course NOAA is not the only agency dealing with these types of issues. Just this morning, Space.com reported that all indications are that the earth science and climate research programs at NASA’s renowned Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) are being dismantled under cover of the government shutdown and in spite of Congressional signs of support for the center’s work through its appropriations processes. The types of actions being used — and that could potentially be used in the upcoming fiscal year — by the administration are exactly what I am concerned about happening to NOAA’s research line office, the Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research. On the emergency management side of all of this, FEMA is of course dealing with its own challenges as discussed in this piece yesterday by the Federal News Network.

One of the comments on my New York Times op-ed called me out for not explicitly condemning climate change in the piece and calling for action on it. While I certainly think that climate change is playing a key role in worsening weather and water related disasters, climate change is not my area of expertise. Weather forecasting and research, warning communication and emergency management are my areas of expertise, and everything I have talked about here today makes me gravely concerned for the state of those efforts today and in the future in this country for all of the reasons I have outlined. Furthermore, even if and when we get more of a handle on climate change, weather and water related disasters will continue regardless, and we need to have robust capacity to forecast, prepare for and respond to these events.

I will continue to try to raise awareness of these issues through all the means I have. Comments on this piece are open for all subscribers, free and paid, given that I hope people will be willing to share their own questions and concerns about these important issues.

Leave a comment