And why this demonstrates how much more we need to be doing as a society to reduce weather fatalities

Dec 03, 2025

In an e-mail to parents yesterday, Camp Mystic — the youth camp where 27 campers, counselors and employees died in the catastrophic July 4th flash flood along the Guadalupe River in the Texas Hill Country — announced new safety plans as it works to reopen its location at Cypress Lake. This location is separate from the camp along the Guadalupe where the fatalities occurred, and it was not damaged in the July 4th flood. NBC News reported that the new safety plans include installation of over 100 flood monitoring units along the north and south forks of the Guadalupe River, two-way radios in every cabin that will also receive weather warnings from the NWS, new backup generators for the camp, and satellite backup for the camp’s internet access.

Obviously, all I know about Camp Mystic’s plans are based on media reporting, but these seem like reasonable initial steps. However, I would hope that these are in fact just initial steps, and that the camp is working closely with emergency management and engineering professionals who are helping develop robust action plans for the camp to implement in the event of a flash flood, as well as providing a realistic evaluation of the risk to the camp from flash flooding.

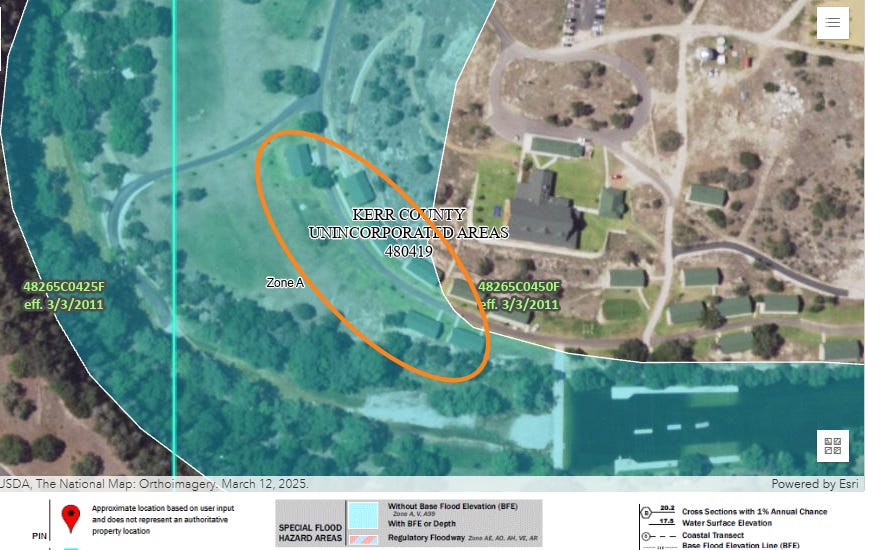

Camp Mystic Cypress Lake is located south of the camp’s Guadalupe River facility where the damage and casualties occurred on July 4. It is situated along Cypress Creek, a tributary of the Guadalupe. In the FEMA flood map above you can see that there are several buildings (highlighted in orange) within the confines of the 1% (or base or 100-year) incidence floodplain for Cypress Creek. Again, the 1% floodplain outlines the area at risk of a flood with a 1% chance of occurrence in any given year — over a 25 year period, there is a 22% chance such a flood will occur.

While these camp buildings are not in the more heavily regulated floodway, as I discussed in my latest post about this event from a couple of weeks ago, it would seem pretty clear to me given the vulnerability of this region to historical catastrophic flash floods, one would want to have robust safety plans that would support being able to move people quickly to higher ground from buildings in or near the 1% floodplain. Obviously, this does not just apply to Camp Mystic – it applies to facilities all along the Guadalupe and other Hill Country rivers; and as we saw on July 4th, that 1% floodplain is only the area at highest risk — floods can and will occur at levels beyond the 1% exceedance level.

In my post a couple of weeks ago, I discussed my strong feeling that the emergency management, weather, social science and engineering communities need to prioritize a collaboration to develop flooding terminology and educational materials that will help bridge communication gaps about flash flooding that clearly exist. An important part of this educational effort that this release of new safety plans by Camp Mystic reinforces for me is the need to help people understand the relative risk of various threats, and for our society to treat them accordingly.

For example, while sources vary in the exact numbers, it seems clear that the odds of a commercial airline crash are astronomically low, somewhere in the neighborhood of .000001% or 1 in 10 million. Even with these extremely low risks, every commercial flight in this country starts with a detailed explanation from the flight attendants about the safety features of the plane and how to evacuate in the event of an emergency. We also have an entire federal government apparatus dedicated to improving safety of aviation, including the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) whose work over the decades has made the already low risk of commercial airline even lower.

Clearly, someone camping along the Guadalupe River has many orders of magnitude of higher risk to be impacted by a life-threatening flash flood than someone flying in a commercial airliner does of being involved in a plane crash – and to be clear, these sorts of flash flood risks exist along numerous rivers around the country. However, we as a society do not treat the flash flood risk — or risks to life from other types of extreme weather — with anywhere near the level of organized mitigation that we do aviation safety.

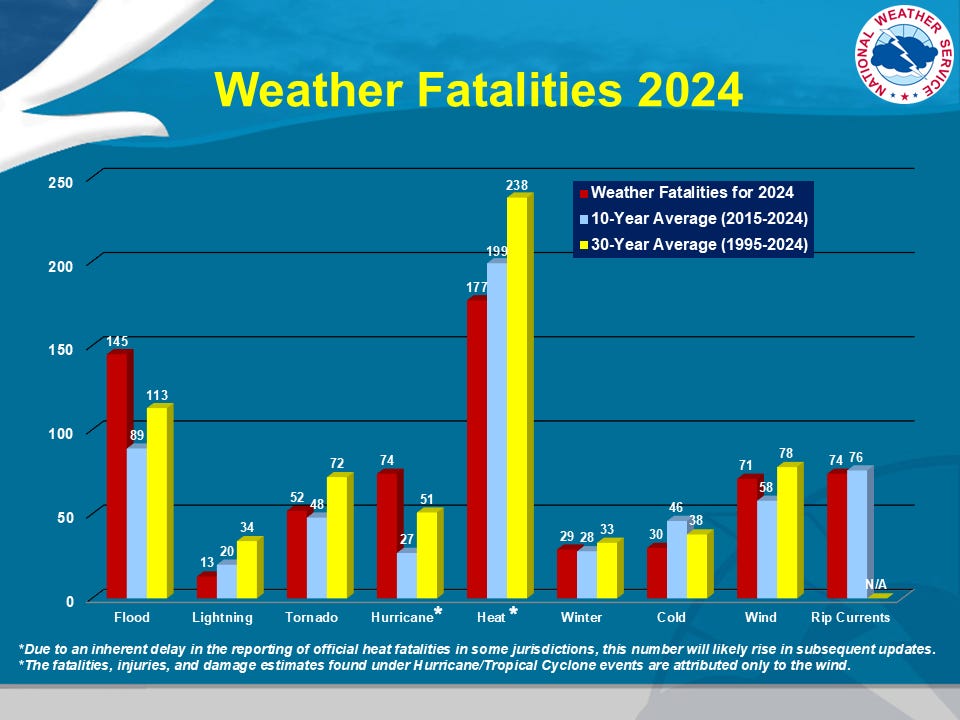

Before the late January midair collision of a military helicopter and American Airlines flight near Washington National Airport took 67 lives, the total numbers of lives lost in commercial aviation incidents in the United States back to 2010 numbered no more than a few dozen. Over the same time period, NOAA/NWS statistics indicate that nearly 10,000 people have died due to extreme weather in this country; in 2024 alone (above) 721 died.

In spite of the incredible difference in total fatality numbers between aviation and weather disasters, our societal approach to these disasters is radically different. Aviation incidents like the fatal January plane crash receive an intense investigation by the NTSB with specific recommendations to improve safety, while events like the July 4th flash flood with 119 fatalities rely on entities like Camp Mystic self-policing themselves and developing their own plans to try to improve safety.

Clearly, if we are serious about reducing extreme weather fatalities in this country, this overall mindset has to change. In recent years, a number of my colleagues in meteorology and emergency management have been advocating for the establishment of a National Disaster Safety Board (NDSB) along the lines of the NTSB to investigate natural disasters and develop recommendations to improve safety, mitigation, warnings and response. While there have been some steps in Congress in recent years to try to establish such an entity, to date it has not happened.

Establishing an entity such as the NDSB clearly needs to be a priority. While I alluded above to the fact that right now entities such as Camp Mystic are self-policing, to be fair right now federal entities such as FEMA and the NWS are in many ways self-policing, and that needs to change too. For too long the work on improving weather warnings, disaster response, etc. has relied upon the responsible agencies developing their own improvement plans, often with limited collaboration or coordination between those agencies.

In my opinion, whether it comes from an NDSB or some other overarching organization, the only way we will make serious reductions in loss of life from weather events like flash flooding is with collaborated, comprehensive cross-agency plans to improve warnings, mitigation and education. Then, the responsible federal agencies must be held accountable for meeting the goals outlined in these plans.

Not only should such an effort be cross-agency, it must also be cross-disciplinary, with meteorology, emergency management, social science, engineering, hydrologists (and others I am sure am missing) all involved. Finally, we cannot continue to take steps backwards with regard to federal investment in science and emergency management. Those investments need to continue — but they also need to be made within the framework of collaborative, comprehensive planning I have described. This is how we start to truly make events like July 4th much less likely to happen and reduce their tragic consequences.

Leave a comment